I read an article yesterday on Bloomberg: “Yale to Be Paid Interest on Dutch Water Authority Bond From 1648.” That’s amazing!

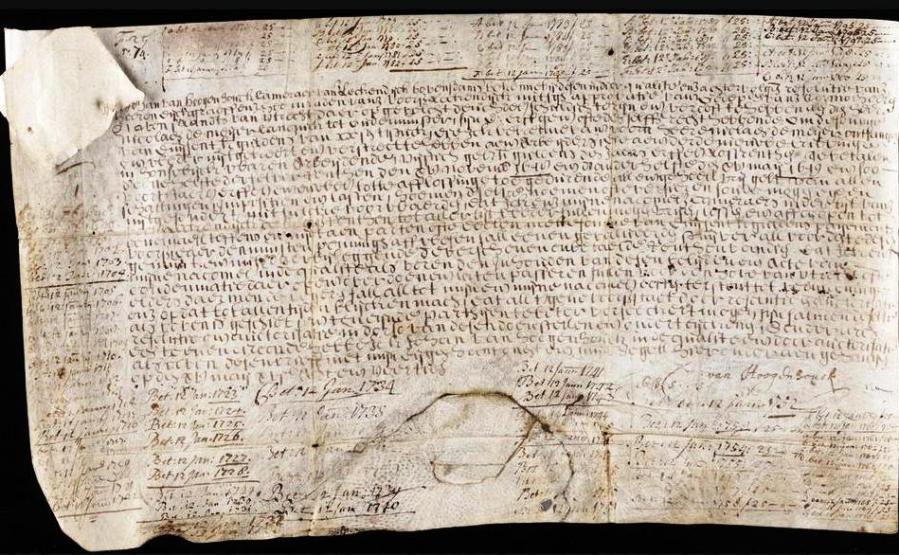

Twelve years ago, Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library purchased a bond issued by a Dutch water authority, the Water Board of Lekdijk Bovendams, in 1648 to fund the reconstruction of the dyke running along the Lek River near the town of Honswijk. Dikes are, and have been crucial for existence and survival of the Netherlands since 55 percent of the surface area is susceptible to flooding from either the sea or from rivers. The water board used the money raised to pay workers at a recently constructed cribbinge, a series of piers near a bend in the river that regulated its flow and prevented erosion.

The water board of Lekdijk Bovendams was founded in 1323 by the bishop of Utrecht and was later managed by the king, until 1971 when it was merged with a number of other water boards into the water board Kromme Rijn, which itself was later merged into the current water board de Stichtse Rijnlanden.

The 1,000 Carolus guilder-bond ($512) was issued at 5 percent interest on May 15, 1648 to Mr. Niclaes de Meijer. The currency in use in 1648, Carolus guilder worth 20 stuivers has been succeeded by the Flemish pound, then the guilder and finally the euro. The bond now pays 11.34 euro ($12.80) annually, which is the modern equivalent of 25 guilders, the interest rate having been reduced to 3.5 percent and then 2.5 percent during eighteenth century (Krantz, Steven G. and Harold R. Parks, Mathematical Odyssey: Journey from the Real to the Complex, Springer, 2014, p.32).

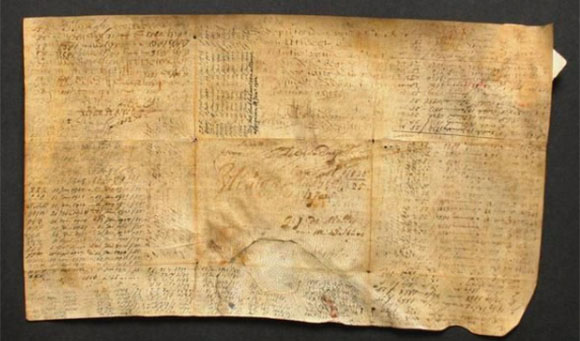

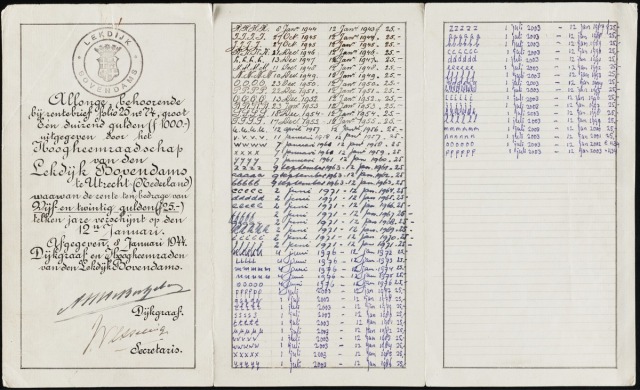

The 1,000 Carolus guilder-bond, which is written on goatskin, is among five of the world’s oldest bonds that still pay interest. The document is a bearer bond, meaning the issuer needs to see it before paying out interest. The issuer will then write the payment date on the document. Interest payments were continuously recorded on the vellum document. By 1944, there was no longer any space on the vellum to list interest payments. A paper allonge was added to record new payments. The last recorded payment was collected July 1, 2003. Geert Rouwenhorst, professor of corporate finance and deputy director of the International Center for Finance, took the bond to the Netherlands to collect 26 years of back interest. That was the last time interest was collected.

Over the centuries, the bond has crossed hands and oceans. Yale University paid 24,000 euros to acquire the bond in 2003 as an artefact. The bond is actually older than Yale itself, which was founded in 1701. The university hasn’t been paid interest since the acquisition. The thing is, the bond pays out in perpetuity, and that water authority still exists, so Yale checked to find out whether it was still earning interest. Yes, it is! The interest has accumulated since Yale acquired the bond in 2003. Yale will receive 136.20 euros ($153) in interest from Dutch water authority de Stichtse Rijnlanden.

In recent years, at least four seventeenth-century bonds issued by Hoogheemraadschap Lekdijk Bovendams — a Dutch water board responsible for upkeep of local dykes — have been presented to the successor organisation (namely, Dutch water authority de Stichtse Rijnlanden) for payment of interest. The oldest of these bonds dates from 1624 (Krantz & Parks, 2014).

The Lekdijk Bovendams, a 33 kilometer long dyke from Amerongen to Vreeswijk, protects large parts of Holland and Utrecht against the water. After a dyke burst in 1624, the water board decided to issue interest letters (bonds) in order to finance restoration. As per Financial Post, the oldest known bond in the world that still produces interest is the perpetual debt worth 1,200 guilders, issued in 1624, of the Lekdijk Bovendams water board. The bond was purchased in 1624 by a Dutch woman, Elsken Jorisdochter, who picked up a 6.25% issue of water company Lekdyk Bovendams Company for 1,200 florins. The bonds purchased by her were still paying interest at the rate of 2.5 percent in mid-twentieth century. The bonds were finally traded and redeemed on the New York Stock Exchange by the heirs of Ms. Joridochter in 1957. The promise was kept.

Although the Dutch bonds are the oldest perpetuities still in existence, the first perpetuities date from much earlier times. For example rentes, which were form of perpetuities and annuities, were issued in the 12th century in Italy, France and Spain. These were initially designed to circumvent the usury laws of the Catholic Church because they did not require repayment of principal, in the eyes of the church these were not considered loans.

There have been many instances in history when institutions issued debt with very long tenure. In the 17th century, people sometimes issued perpetual debt. But it is very rare that there is an uninterrupted history when governments or other entities have not defaulted on those debts.

wow…this is amazing!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Amazing!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Amazing!

LikeLiked by 1 person

OMG…. Amazing

LikeLiked by 1 person