March 21 is a public holiday in Iraq to mark the celebration of the Kurdish New Year – Nowruz. This year, the Iraqi government declared Thursday, March 22 also a public holiday. It’s, therefore, a long weekend for us. We decided to visit the National Museum of Iraq, aka the Iraqi Museum on Thursday.

The National Museum of Iraq is the cultural epitome of historically rich Iraq. Established in the 1920s in Baghdad, the museum originally contained nearly 300,000 precious historical relics ranging from the Neolithic Age up to 100,000 years ago to the mid-19th century.

The museum staff is very polite and cooperative. One museum official gave us a map of the museum to guide us through various halls in this two-storied museum dedicated to the collection and interpretation of the history of Iraq and its environs. The collections consist of mainly man-made objects covering the past 5,000 years and more. The types of objects in the collection represent Sumerian, Akkadian, Assyrian, Babylonian and Islamic cultures and include objects made of stones, glass, pottery, metal, ivory, and parchment, among others. Museums are an important means of cultural exchange, enrichment of cultures.

HISTORY OF THE MUSEUM

According to the American Journal of Archaeology, the Iraq Museum was founded in 1923 when Gertrude Bell, the British woman who helped establish the nation of Iraq, stopped the archaeologists from taking out of the country all of his extraordinary third-millennium BCE finds from the ancient Sumerian city of Ur (esp. the jewellery of the royal cemetery) for division between the British Museum in London and the University of Pennsylvania’s Museum in Philadelphia. She believed that the Iraqi people should have a share of this archaeological discovery made in their homeland and, thereby, started a museum in central Baghdad, pressing into service two rooms in an Ottoman barracks as its very first galleries. Later on, the museum was shifted to this new premises and formally opened in 1966.

PLUNDERING OF HERITAGE

The protection of a museum’s holdings in times of warfare or civil unrest is a multifaceted and complicated issue. Because museums present themselves as storehouses and display venues of treasure, they become targets of looting by organised gangs and by people from the street.

In the chaotic, violent April of 2003, as US tanks rolled into Baghdad, the Iraq Museum was broken into and pillaged. Looters rampaged through the halls, storerooms, and cellars, stealing more than 15,000 precious objects. Iraqi officials estimate that as many as 137,000 pieces, in addition to 15,000 registered artefacts, were looted from the museum and archaeological sites across the country.

Ironically, centuries after many of the remains of these ancient cultural entities were looted by European colonial forces in order to fill grand national museums, we are seeing a 21st-century version of cultural colonialism. Private collectors are enabling an entire economy of illegal activities.

Despite the chaotic situation and rampant plundering of Iraq’s cultural heritage, the restored museum still harbours unique items that have been recovered, including the Warka vase, which reflects Sumerian philosophy of life and death; the Warka Lady’s stone head; and the Sumerian guitar, the most ancient musical instrument in the world. The collections of the National Museum of Iraq include art and artefacts from ancient Sumerian, Babylonian, Akkadian, Assyrian, and Chaldean civilizations.

The Iraq Museum is still one of the best archaeological museums in the world, containing material evidence for the development of civilised human society from the very beginning of its history.

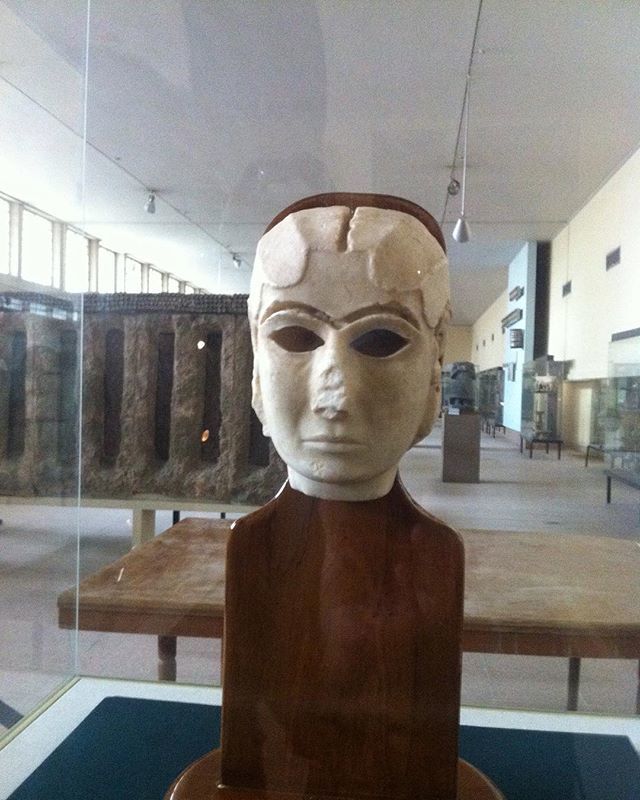

THE LADY OF WARKA

There was a conference also going on the “The Lady of Warka”. The “Lady of Warka” a.k.a. the “Mask of Warka”, dating from ca. 3100 BCE, is one of the earliest representations of the human face. The carved marble female face is probably a depiction of Inanna – the ancient Sumerian goddess of love, beauty, sex, desire, fertility, war, combat, justice, and political power. She was later worshipped by the Akkadians, Babylonians, and Assyrians under the name Ishtar. The Mask of Warka is unique in that it is the first accurate depiction of the human face.

HATRA

Hatra (Al-Hadr in Arabic) is located in the Al-Jazira region between the rivers Tigris and Euphrates. Their written language was Aramaic. Hatra is believed to have been built by the Assyrians or possibly in the 3rd or 2nd century BCE under the influence of the Seleucid Empire.

Hatra flourished under the Parthians, during the 1st and 2nd centuries CE, as a religious and trading centre. The remains of the city, especially the temples were Hellenistic and Roman architecture blended with Eastern decorative features, attest to the greatness of its civilization.

ASSYRIA

Nabu is the ancient Mesopotamian patron god of literacy, the rational arts, scribes, and wisdom. Nabu was worshipped by the Babylonians and the Assyrians. Nabu replaced Nisaba in the Sumerian pantheon and gained prominence among the Babylonians in the 1st millennium BCE when he was identified as the son of the god Marduk. He was also the inventor of writing and a divine scribe. Due to his role as an oracle, Nabu was associated with the Mesopotamian moon-god Sin.

A big pottery jar with Barbotine decorations with designs and motifs of lion heads, animals, human face, plant and geometric motifs found in Mosul belonging to the fourteenth century.

We were unlucky as Babylon Hall was closed for maintenance and documentation. I may have to visit again, at least for the Babylon Hall. This time my main attraction was the Lamassu, about which I have written a separate article.

Indeed it does look like one of the best museums for ancient history.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes, Arvind and it would have been much better had it not been looted.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Absolutely!

LikeLiked by 2 people

It is interesting to know that a British lady helped to establish the Museum of Iraq and stopped the archaeologists from taking out of the country all the treasured artefacts. I am of the opinion that a country’s artefacts should remain within a country.

Yet, though I may never get a chance to see the museum of Iraq, I can relate to some of these artefacts as many of these were present in the Museum of Pennsylvania and the British Museum, and I had a chance to visit both these museums.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes, I am also of the same opinion that relics of the country must remain with them. But most of the important relics are in the British museum, Louvre or in the Universities of the US. They took the advantage of the western imperialism in the 19th and 20th centuries.

LikeLiked by 2 people

True that. Louvre, Paris is on my wishlist,

LikeLiked by 2 people

Hello, Indrajit. Your post reminds me the memory of reading the history book of school days.Babylon, The Mesopotamia civilization, etc hit my brain to remember the story of the civilization. I don’t know, whether I can visit Iraq or not. But, from now I’m including Iraq travel on my bucket list. Very nice post.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Iraq is full of history. Unfortunately, many historical sites have been damaged, lost. The situations are improving in Iraq. I wish you can make it to Iraq one day.

LikeLike

Pingback: 10 coisas importantes que foram destruídas pela guerra | Brasilempauta.com

Pingback: 10 Important Things That Were Destroyed by War - Random Review

Pingback: 10 Important Things That Were Destroyed by War - Billionaire Club Co LLC

Pingback: 10 coisas importantes que foram destruídas pela guerra - Brasil em Pauta Notícias