Food has always been an integral part of human existence. From hunting and gathering to agriculture and domestication, humans have evolved alongside their food sources. The oldest known cookbook, discovered in Ancient Mesopotamia, sheds light on the culinary traditions of one of the world’s earliest civilizations.

Mesopotamia, located in present-day Iraq, was home to a complex society that flourished between 4000 BCE and 539 BCE. The Mesopotamians were skilled farmers and traders who relied on the fertile land between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers to grow crops such as barley, wheat, and lentils. They also raised livestock such as sheep, goats, and cows for meat, milk, and cheese.

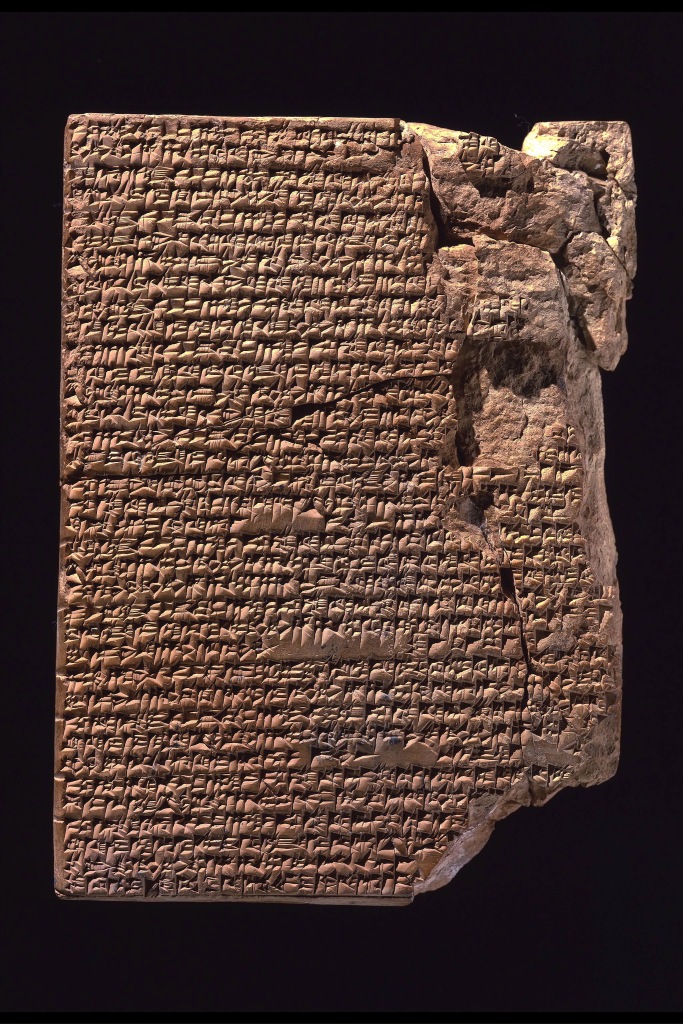

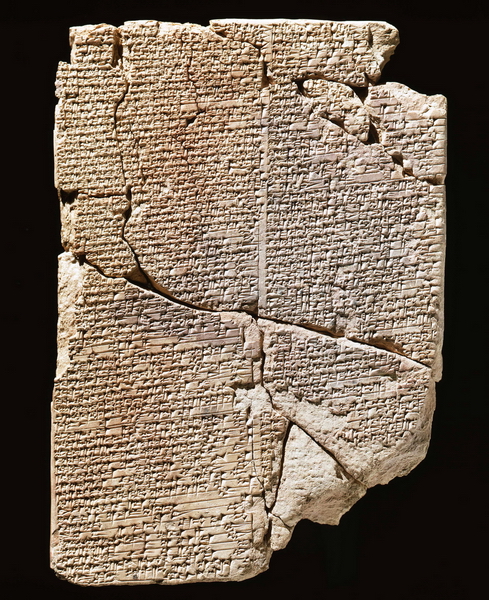

The Mesopotamian recipe book is the oldest and the first documented cuisine in the world, of which only three Babylonian cuneiform tablets are extant today (housed at the Babylonian Collection of Yale University). It’s a set of cracked tablets engraved by an early civilization’s version of a master chef going back to 1700 BCE. The three Old Babylonian tablets were not written by the same hand, and a physical analysis of the clay shows that it originated from at least two different sources. The tablets all list recipes that include instructions on how to prepare them.

The cookbook contains a collection of recipes for various dishes and beverages, including stews, soups, bread, beer, and wine. Some of the recipes are surprisingly similar to modern-day dishes, such as a lamb stew seasoned with onion, garlic, and coriander.

One of the most interesting aspects of the cookbook is the use of spices and herbs. The Mesopotamians were known for their love of flavor and aroma, and they used a wide range of ingredients to achieve this. Some of the spices mentioned in the cookbook include cumin, cardamom, saffron, and cinnamon. Herbs such as mint, parsley, and cilantro were also commonly used.

Comparing the Babylonian recipes to what we know of medieval cuisine and present-day culinary practices suggests that the stews represent an early stage of a long tradition that is still dominant in Iraqi cuisine. Boiling the meat into stew with spices and other ingredients was the basic culinary technique. Iraqi Pacha is prepared almost in similar ways as are described in the tablets.

The earliest cookbooks found around the world give people today a fascinating look at not only what the people of the time ate but also their lifestyles, mainly of those from the upper class. It’s hard to compare modern Middle Eastern cuisine with its ancient predecessors — for one, the Babylonians appear to have been fond of pork, which is forbidden by Islam and virtually nonexistent in modern Iraq.

Archaeologists have found three small clay tablets inscribed with intricate cuneiform signs, although damaged to different degrees, which provide cooking instructions for more than thirty-five Akkadian dishes. Cuneiform was at first written in the Sumerian language. The recipes are elaborate and often call for rare ingredients. They represent Mesopotamian haute cuisine meant for the royal palace or the temple and also a fairly accurate picture of the standard Mesopotamian diet. The ancient cookbooks contain recipes for 21 types of meat dishes and 4 kinds of vegetable ones, almost all of which involved combinations of meat, fowl, vegetables, or grain cooked in broth, which had first been flavored with onions, garlic, and leeks. The dishes were slow-cooked in a covered pot to make the food extra tasty.

Instructions call for most of the food to be prepared with water and fats, and to simmer for a long time in a covered pot. Ancient foodies seem to have preferred fowl and mutton. Babylonian chefs had easy access to meat, as Mesopotamian farmers had been raising sheep and chicken since prehistory. Meats included stag, gazelle, kid, lamb, mutton, squab and a bird called tarru (believed to mean fowls). Fish were eaten along with turtles and shellfish. Various grains, vegetables and fruits such as dates, apples, figs, pomegranates and grapes were integral to diet. Roots, bulbs, truffles and mushrooms were harvested for the table. Frequently mentioned seasonings included onions, garlic and leeks, while stews were often thickened with grains, milk, clarified butter, fats, beer or animal blood. Salt was sometimes mentioned. Scholars have not been able to identify all the ingredients.

The use of animal intestines is said to have been perfected by the Sumerians, who are credited with the invention of sausages about 4000 BCE. Babylonians made spicy sausages with minced meat, stuffing the mixture into animal intestines to act as skins in approximately 1500 BCE.

The dishes mentioned in these tablets were probably not the kind of food that was commonly consumed by the average ancient Mesopotamian. This is due to the fact that the ingredients required for the dishes were not easily obtained by the ordinary person. Moreover, the instructions for the preparation of these dishes are quite elaborate. Therefore, it is likely that it was the elites of Mesopotamian society who savored these dishes, perhaps on some festive occasion.

The cookbook also provides insight into the social and cultural significance of food in Mesopotamia. Many of the recipes are associated with specific festivals and ceremonies, such as the New Year’s feast. Food was not only a means of sustenance but also a way to celebrate and honor the gods.

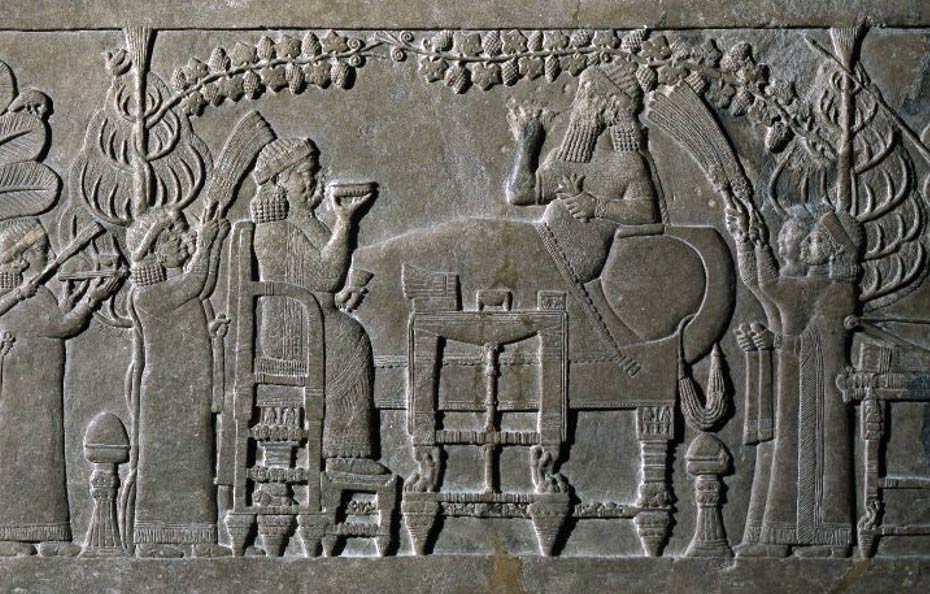

Mesopotamia had its share of legendary feasts. A banquet held in the ninth century BCE. by the Assyrian King Ashurnasirpal II, according to records found inscribed on a brick, drew 69,574 guests. Over 10 days they consumed 25,000 lambs and sheep, 500 stags, 500 gazelles, 30,000 birds, 10,000 eggs, 10,000 loaves of bread and thousands of gallons of wine and beer.

The oldest cookbook from Ancient Mesopotamia offers a fascinating glimpse into the culinary traditions of one of the world’s earliest civilizations. It highlights the importance of food in Mesopotamian society and provides evidence of their advanced knowledge of cooking techniques and flavor combinations. As we continue to explore the history of food, we can appreciate the legacy left behind by these ancient cooks and the impact they have had on our modern-day cuisine.

Nice post. So people mainly used to eat stew!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Nilanjana.

LikeLike

everyone with good sense still mainly eats stew

LikeLiked by 1 person

Quite true. Thanks for dropping by.

LikeLike

I don’t think I have the guts (literally) to have Pache!!!🤪😜

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, it’s not for everyone. You need to be a bit adventurous in eating.

LikeLike

I would love to taste and eat an actual food prepared using one of those Mesopotamian recipes from thousands of years ago. That would be a genuine ancient experience.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Absolutely. But, I wonder whether the same experience is possible. There are some dishes still available e.g. Pache, Masgouf dating back to that era, but there have been some modifications in recipe or the cuisine over the period.

LikeLike