It was an ordinary evening at the regional office—the kind where the sun slips lazily toward the horizon, painting the tiled floor in golden stripes, and the staff begins that slow, hopeful ritual of shuffling papers just loudly enough to imply productivity while mentally planning dinner.

Inside his cabin, Mr. Goel, our ever-diligent Regional Manager, sat hunched over neatly arranged files. His pen moved with mechanical precision, the man himself embodying the discipline of a railway timetable. Nothing, absolutely nothing, escaped his administrative radar.

And then the phone rang.

Not the polite, chirpy ring of a desk phone—but the sharp, metallic trrriiing that only official landlines in Indian offices can produce. The kind of ring that carries foreboding. The kind that tells you dinner will be late tonight.

The call was from the Zonal Office. More specifically, the Zonal Manager’s Personal Assistant—an individual whose voice alone could alter the heart rate of any regional staff member.

“The Zonal Manager will visit tomorrow at 4 pm.”

Sixteen words. And just like that, the atmosphere shifted from evening calm to controlled chaos.

Mr. Goel stepped out of his cabin with the gravitas of a general about to brief his battalion. An emergency meeting was summoned. Files were snapped shut. Teacups abandoned. Backrests straightened. And the grand announcement was made.

The Zonal Manager was coming.

These visits were not routine. They were seismic events. They could reshape careers, tilt annual reviews, and sometimes send a man in search of transfer forms.

The mandate was clear:

All city managers must attend.

The presentation must be flawless.

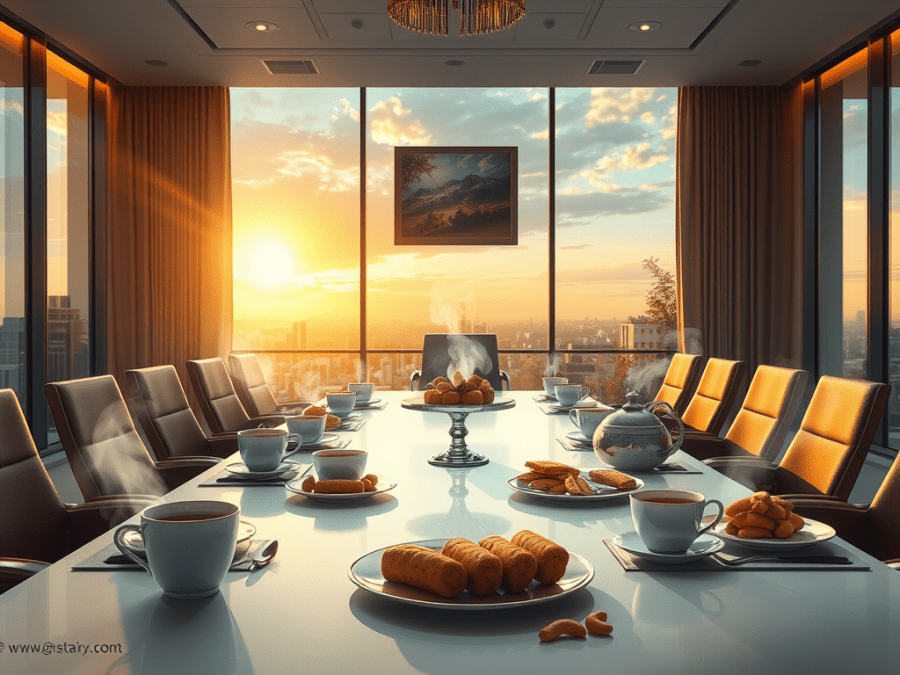

And—of vital importance—a high tea must be arranged.

Now, arranging high tea in a small town is not the logistical equivalent of calling a hotel and saying, “Send pastries.” This is a delicate ecosystem involving locally available supplies, hurried negotiations, and a silent prayer to the gods of bakery inventory.

The P.A. had listed the menu: tea, cashews, samosas, pastries, biscuits.

Pastries?

That was ambitious. Pastry in a small town often meant a lopsided cream roll sitting behind a glass counter hoping someone would show mercy.

Mathur Sahib, the practical one among us, suggested, “Let’s keep a cake instead.”

Saxenaji, an apostle of local flavours, leaned in conspiratorially and said, “Yasin’s kebabs. They’re famous… and the Zonal Manager likes meat.”

The room nodded in unison. Kebabs it would be. And just like that, the meeting disbanded with everyone assigned a mission.

My task was the PowerPoint—the holy grail of modern bureaucracy. Deposits, loans, growth, slippages, targets achieved, and all the other corporate hieroglyphs that make senior officers smile or frown. Mr. Goel’s expectations were legendary. Every digit had to be verified, every bar chart aligns perfectly, every slide transition behaves as if it had been trained in etiquette.

While I wrestled with pivot tables, the rest of the office plunged into a deep-clean frenzy. Tables gleamed, files were reborn into neat stacks, reports were bound with devotional sincerity. For a few hours, we resembled an army preparing for inspection by a monarch.

At exactly 4 pm the next day, the Zonal Manager arrived. His demeanour was part benign, part inscrutable—like an elder who could bless you or disown you depending on the next sentence you uttered.

The presentation rolled out smoothly. Slide after slide narrated our regional journey. The Zonal Manager watched with clinical focus, interjecting with precise, pointed questions. Mr. Goel fielded them with calm poise.

By 5:30, high tea was served.

It was a glorious spread—samosas still warm, cashews neatly arranged, biscuits crisp, the cake dignified… and at the centre of the table, shimmering in their oily magnificence, Yasin’s famous kebabs.

The Zonal Manager took a bite.

A smile emerged.

A rare, precious smile.

The room exhaled in collective relief. Even Mr. Goel, a strict vegetarian, allowed himself the luxury of a faintly satisfied nod.

And then—like all great tragedies—it happened.

In a moment of relaxed conversation, Sharmaji, perhaps emboldened by the atmosphere, said casually: “I’ve heard Yasin Bhai makes these kebabs with buffalo meat.”

The words dropped into the room like a brick into a silent pond.

The Zonal Manager’s smile vanished.

Mr. Goel’s face transitioned from relief to alarm.

Silence descended—the heavy, suffocating kind.

Sharmaji, realizing the magnitude of his verbal misfire, looked stricken. But words, once released, cannot be dragged back like errant files.

The spell was broken. The warmth in the room evaporated. Bhatiaji, who had overseen the arrangements, looked as if someone had erased his increments. Saxenaji stared into the table, guilty for ever suggesting kebabs. The rest of us wished we could melt into the floor tiles.

The Zonal Manager left soon after. Polite, but distant.

As we shut down computers and gathered our belongings, the weight of the moment lingered, heavier than any PPT file we had compiled.

On the ride home, I replayed the scene again and again. Hours of preparation… undone by a single unguarded sentence.

And then it struck me—success in an office, much like in life, rests not only on effort or precision, but on an intangible element we often ignore:

Timing.

What is spoken—and when—can determine whether a kebab becomes a triumph… or a turning point.

That evening, I remembered an old saying:

“Vachan se bada koi prasad nahin,

Aur vachan se bada koi shastra nahin.”

Words can bless.

Words can wound.

And unlike kebabs, words linger long after the plates are cleared.

An unrelated question – the image seems unnatural, esp the faces. Is this what they call an AI generated image?

LikeLiked by 2 people

I generated this AI imagined image using Meta. You can spot the “Imagined with AI” Meta logo in the bottom left corner.

LikeLike

Thanks. Though I cannot locate the “Imagined with Meta” on the image.

LikeLiked by 1 person

When accessing the post, the featured image appears clipped. However, if you visit the blog site directly, you can view the full image, including the logo. You can check it out at: https://indroyc.com/. If you access the post on your mobile, you can see the full image, with the logo visible.

LikeLike

This is the reason why a spoken word is sharper than the sharpest sword. One should measure their words before speaking, especially in an official gathering.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re right, Aranjit. Thank you for reading and comment.

LikeLike

Nice anecdote! It’s true words should be carefully chosen otherwise it can cause disasters.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, Sanchita.

LikeLike