I was always drawn to the grand, sweeping narratives of history. Like many of us, when I closed my eyes and pictured the “dawn of civilization,” I saw pharaohs in gleaming gold, fire-wielding warriors carving out empires, or perhaps a brooding poet, quill in hand, capturing an age-old epic. I imagined that the very first name to survive the long, silent march of time would belong to someone monumental—a king immortalized in triumph, or a god-like sage.

I was wrong. Delightfully, profoundly wrong.

The deeper I delved into the digital dust of ancient archives, the more a quiet, almost anticlimactic truth emerged: the first recorded personal name in history belongs not to a conqueror, but to an accountant.

His name was Kushim.

An accountant. The word itself feels almost anticlimactic, doesn’t it? It conjures images of ledgers and numbers, of meticulous record-keeping, a world away from the grand narratives we often associate with the dawn of history. My initial reaction was one of slight disbelief. Could it truly be? Would the very first named person in history be someone whose daily life revolved around the seemingly mundane task of tracking goods?

It made me pause and reconsider my own assumptions about history, about who gets remembered and why. We are so often drawn to the dramatic, the monumental. We celebrate victories and lament defeats, we marvel at artistic genius and political prowess. But what about the quiet, consistent work that underpins the very fabric of society? What about the individuals who, through their diligence and attention to detail, helped to build and maintain the complex structures of early civilizations?

This revelation sparked a new kind of fascination within me. It was a reminder that history is not just a tapestry woven with the threads of grand events and famous figures. It is also composed of countless smaller threads, the individual lives and contributions of people whose names we may never know, or in this extraordinary case, whose name we know but whose story we are only beginning to understand.

And then, as I continued my research, something even more remarkable happened. It wasn’t just that the first recorded name belonged to an accountant. It was that, in a way, I felt a strange connection to this individual, this pioneer of record-keeping. It was as if their story, however fragmented, was reaching out across the millennia.

So, let me tell you his story. Or rather, let me tell you my story, as I imagine it might have been. Because the truth is, the first name etched into the annals of recorded history is a simple one: Kushim.

Imagine a world vastly different from our own. The year is approximately 3200 BCE. The great civilizations of Mesopotamia are beginning to take shape in the fertile lands between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. The air hums with the energy of burgeoning cities, the sounds of trade and craftsmanship filling the dusty streets. In one such city, likely the bustling hub of Ur, I lived.

I was born long before the concepts of nations as you know them existed. My world was one of city-states, of powerful temples and the ever-present rhythm of the agricultural cycle. Unlike the kings and priests who held positions of authority, my life was centered around a more practical, yet equally vital, role. I was a scribe, an early form of what you would now call an accountant.

Think about it. As societies grew beyond small, self-sufficient communities, the need for organization and record-keeping became paramount. How could the temple manage its vast stores of grain? How could traders keep track of their transactions? How could the rulers administer their growing territories without a system to document resources and obligations? This is where individuals like me came in.

Our tools were simple: damp clay tablets and reeds sharpened into styluses. With these, we painstakingly pressed wedge-shaped marks – cuneiform – into the soft clay, capturing information that would otherwise be lost to memory. It was a slow, deliberate process, each stroke requiring care and precision.

My focus, as far as we can tell from the surviving records, was on barley. Barley was the lifeblood of our society. It was used for food, for payment, even for brewing beer. The Temple of Inanna, a powerful institution in Ur, held vast quantities of this precious grain, and it was my responsibility to keep track of its flow – how much came in from the fields, how much was distributed, how much was owed.

It might sound tedious, but it was a crucial role. Without accurate records, chaos would ensue. Disputes would arise, resources would be mismanaged, and the delicate balance of our society would be disrupted. In my own way, I was contributing to the stability and prosperity of my community.

One day, as I meticulously recorded a transaction, a shipment of barley delivered over a period of thirty-seven months, totaling a significant 29,086 measures, I did something that, unbeknownst to me, would echo through the millennia. At the end of the inscription, I pressed my name into the soft clay: Kushim.

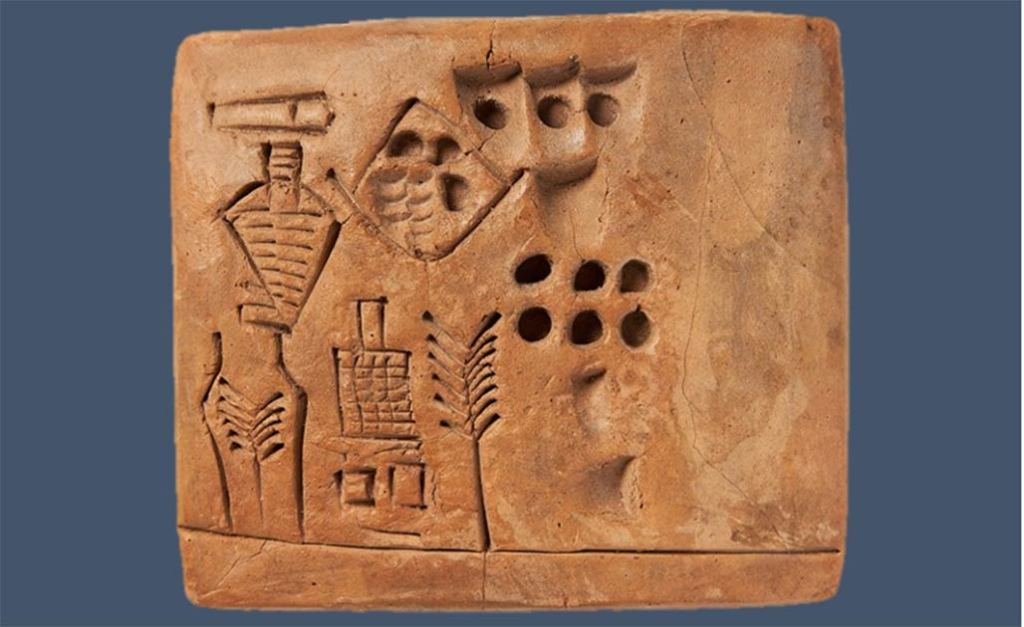

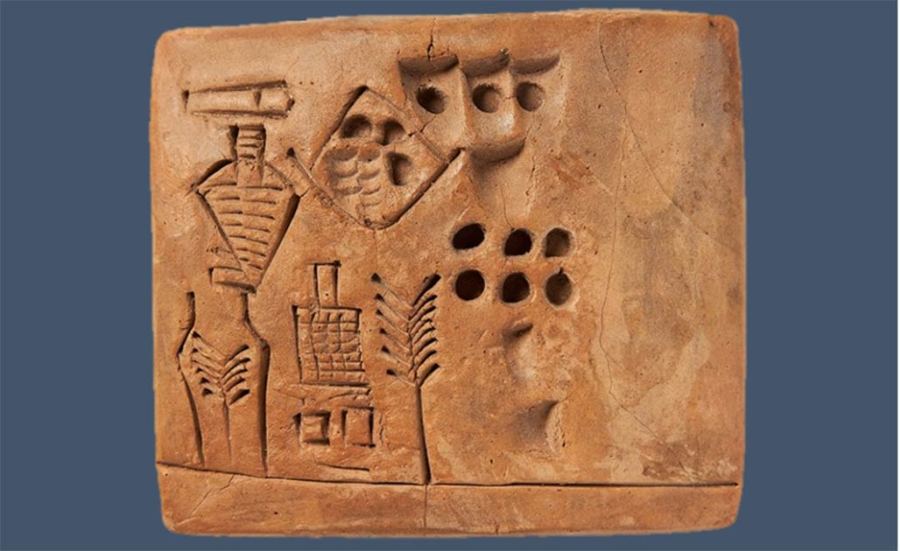

This wasn’t a grand declaration or a boastful signature. It was simply a way to identify the person responsible for the record, a standard practice in our nascent system of accounting. The clay tablet, now known as the Kushim Tablet, was essentially a receipt, a confirmation of the transaction. It stated, in its concise cuneiform script:

29,086 measures barley

37 months

Kushim

The most logical interpretation is: “A total of 29,086 measures of barley were received over a period of 37 months. Accounted for by Kushim.”

Imagine that small, unassuming piece of baked clay. It’s not adorned with elaborate carvings or depictions of heroic deeds. It’s a simple record of grain, bearing the mark of a diligent accountant. Yet, within those unassuming wedge-shaped marks lies a profound significance. It is the earliest known instance of a personal name being explicitly recorded.

This wasn’t a boast or a declaration of war. It was simply the world’s first-known signature, a way to identify the person responsible for the record, ensuring accountability in the burgeoning administrative system of a city like Ur. The simple act of signing off on a shipment of grain secured his unexpected place in the vast, intricate tapestry of human history.

The reason we were even writing in the first place was born out of necessity. Our world had grown too complex for purely oral traditions to suffice. The intricate web of trade, taxation, land ownership, and religious obligations demanded a more permanent and reliable form of record-keeping. Writing was not initially conceived for poetry or storytelling, but for the practical needs of administration and commerce.

I wasn’t the only scribe, of course. In every temple and administrative center, individuals like me were hunched over clay tablets, diligently documenting the flow of goods and resources. We were the unsung heroes of our time, the keepers of vital information. But it is my name, “Kushim,” that has somehow survived the relentless march of time, appearing on not just this one tablet, but on several others, all related to similar transactions involving barley.

It’s a humbling thought to consider that my name, a name belonging to someone who likely never wielded great power or commanded armies, is the first to be etched into the recorded history of humankind. It speaks volumes about the fundamental importance of even the most seemingly ordinary roles in the development of civilization.

Looking back, or rather, imagining myself looking back from that distant era, I realize that we were at the cusp of a monumental shift. The invention of writing was a turning point for humanity. It allowed us to transcend the limitations of memory, to preserve knowledge across generations, and to build increasingly complex societies. And in that crucial development, the work of scribes and accountants like me played an indispensable role.

Perhaps my legacy isn’t one of grand achievements in the traditional sense. I didn’t conquer lands or write epic poems. But I did contribute to the foundation upon which future civilizations would be built. I was part of the machinery that allowed our society to function, to organize, and to grow. And in the simple act of recording my name on those clay tablets, I inadvertently secured a place, however unexpected, in the vast and intricate tapestry of human history.

So, the next time you think about the great figures of the past, remember Kushim, the accountant from ancient Sumer. Remember that even the most seemingly mundane tasks can have profound and lasting consequences. Remember that history is not just about kings and queens, but also about the countless individuals who, through their daily work, shaped the world we live in today. And perhaps, just perhaps, you’ll find a new appreciation for the power of record-keeping and the enduring legacy of a name etched in clay over five millennia ago.

Pinpointing the very first person in written history is quite challenging because the earliest written records date back thousands of years and are often fragmented or incomplete. However, some of the earliest known written records come from ancient civilizations like the Sumerians, who lived in Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq) around 3500-3100 BCE.

In the quiet corridors of ancient Sumer, Kushim left an indelible mark on history, not as a conqueror or ruler, but as an ordinary individual involved in a simple transaction. The Kushim Tablet, dating back to around 3200 BCE, captures a pivotal moment in civilization, marking the birth of written language for practical administrative and economic needs.

In Kushim’s quiet legacy, we glimpse the dignity of everyday lives: clerks, counters, recorders—those who made civilization function. His story reminds us that immortality does not always belong to kings or heroes; sometimes it belongs to the careful hand that preserves memory.

My fascination with Kushim is now tinged with a hope: that one day, an archaeologist or a brilliant linguist will crack the code of the Indus Script. And when they do, the very first name they utter may not be a majestic title from a forgotten epic, but the simple, honest signature of a man or woman who worked with their hands and stylus to keep the city running.

Until then, Kushim stands as a universal, transnational symbol. He is the quiet ghost in the halls of history who reminds us that the immortality of the administrative hand is often more lasting than the shout of the conquering voice.

The first human name we know, etched in clay over five millennia ago, tells a simple but profound truth: Civilization begins with a ledger.

Very informative. I have a feeling that if similar efforts were applied in the subcontinent, probably we would be the oldest civilization and much advanced as well.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, Aranjit. The Indus-Sarasvati cultural tradition represents the beginnings of the Indian civilization. This tradition has been traced back to about 7000 BCE in remains that have been uncovered in Mehrgarh and other sites. The earliest known form of writing in India is the Indus Script, which dates back to the 3rd millennium BCE during the urban phase of the Harappan civilization. This script, used by the ancient Indus Valley Civilization, remains largely undeciphered, leaving many aspects of their written communication a mystery.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Very informative; yet another post with a piece of new information.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, Nilanjana.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Amazing nugget once again. Wondering if the name Kushim has a meaning and if it is popular in modern-day Sumeria 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

The name “Kushim” is uncommon, and its meaning isn’t widely known. However, exploring its linguistic roots hints at its potential origin and significance. As per Hebrew and Arabic languages, “Kushim” appears linked to “kush,” meaning “dark-skinned,” often associated with individuals of African or South Asian descent. Determining the exact meaning and emergence of “Kushim” without further historical or contextual information proves difficult. He could be a Dravidian from South India. 😉😉😄

LikeLiked by 2 people

As usual, very informative. No doubt Sumerian script is the oldest one, perhaps followed by Egyptian script. Tamil and Sanskrit languages were said to be quite old too, approximately 5000 years old (about 3000 BCE). While Tamil was used by Dravidians, Sanskrit was brought in by Aryans. I wonder was Sanskrit that old? It could be true. The first written script in Sanskrit was perhaps Rigveda which was believed to be between 1500 – 1000 BCE. Bramhi came much later, around 1st or 2nd century BCE

Indus script is also dated around 3000 BCE. I have no idea what language was used at that time. The script found in Harappan potteries and tablets are yet to be deciphered. Vedic period came much after IVC, when Sanskrit was used. Thats where my doubt lies…is Sanskrit that old as it is claimed to be?

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, Mano.

As you mentioned, the Harappan script dating back to circa 3000 BCE remains undeciphered, making it the oldest known script in India. However, commonly regarded as the oldest deciphered script in India, the Brahmi script emerged around the 5th century BCE in the ancient Indian subcontinent.

Primarily utilized for inscribing Prakrit and Sanskrit languages, Brahmi script served as a foundational precursor to numerous scripts across the Indian subcontinent, such as Devanagari, Tamil, Telugu, and Kannada, among others. Its significance extends beyond mere linguistic communication; the Brahmi script played a pivotal role in disseminating the teachings of Buddhism and Jainism, serving as the medium for many religious texts.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Would you be interested in a Zoom discussion?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Can you please mention the subject for the Zoom discussion?

LikeLike

The earliest written record?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, as per the discoveries, so far.

LikeLiked by 1 person

When are you available?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Please tell me the purpose of your call or meeting.

LikeLike

Pingback: All The Ghosts You Will Be – Archytele

Pingback: All The Ghosts You Will Be - Furry Refuge Online Furry Community

Pingback: All The Ghosts You Will Be – Newsworthy

Pingback: All The Ghosts You Will Be – arzya

Pingback: All The Ghosts You Will Be - SLOPPBOXX™

Pingback: All The Ghosts You Will Be - Trending Online

Pingback: All The Ghosts You Will Be -