International Literacy Day celebrates the power of reading, knowledge, and education. What better way to honour this day than by delving into the history of the world’s oldest known library? The world’s first great library was the ancient Assyrian King Ashurbanipal II, who ruled an empire that spanned from Iran to Egypt from his Mesopotamian capital of Nineveh in the 7th century BCE. The library’s collection was comprised of some 30,000 clay cuneiform tablets organized according to subject matter. The Royal Library of Ashurbanipal stands as a testament to the enduring human pursuit of knowledge and the preservation of cultural heritage.

Since 1967, the annual celebrations of International Literacy Day (ILD) have taken place on 8 September worldwide to remind policy-makers, practitioners, and the public of the critical importance of literacy for creating a more literate, just, peaceful, and sustainable society. Literacy is a fundamental human right for all. It opens the door to enjoying other human rights, greater freedoms, and global citizenship.

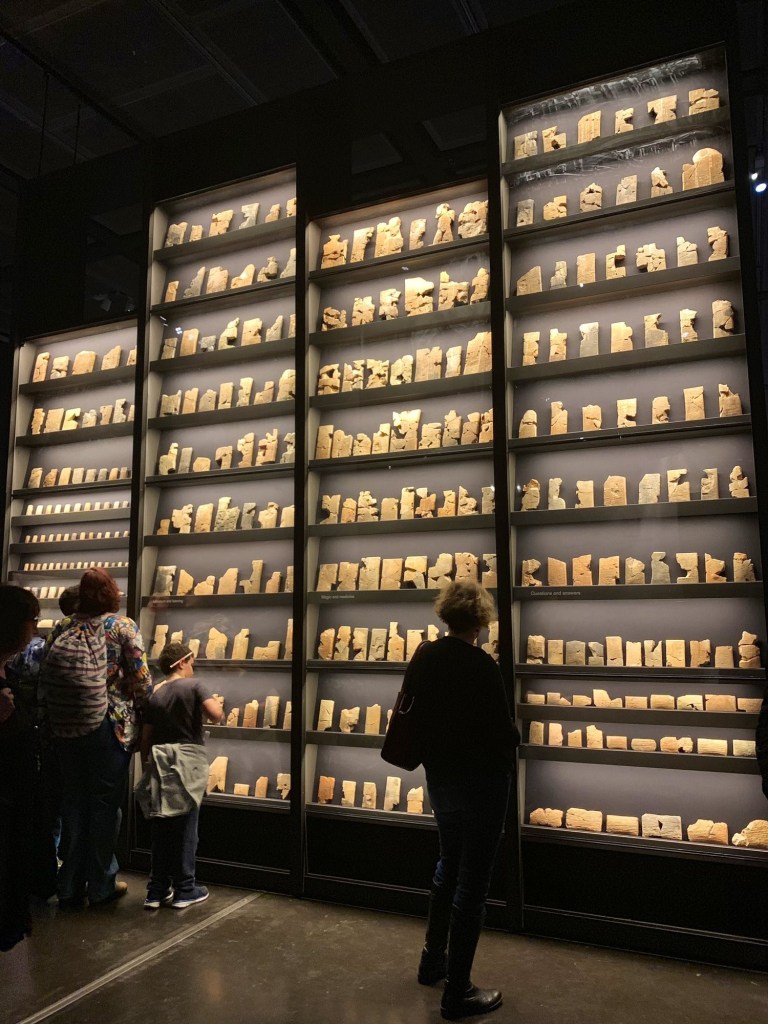

The Royal Library of Ashurbanipal, named after the last great king of the Assyrian Empire, was established for the “royal contemplation” of its eponymous ruler. Situated in Nineveh, in modern-day Iraq, this library was a treasure trove of knowledge, housing approximately 30,000 cuneiform tablets. These tablets were meticulously organized according to subject matter, ranging from archival documents and religious incantations to scholarly texts and literary works. Among its most notable contents was the 4,000-year-old “Epic of Gilgamesh,” a seminal piece of literature that has captivated readers for millennia.

The Royal Library of Ashurbanipal, considered one of the oldest and most significant libraries in human history, offers a remarkable window into the ancient world. Located in the Assyrian city of Nineveh, near modern-day Mosul in Iraq, this repository of knowledge was established by Ashurbanipal, the last great king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. Born in 685 BCE and ruling from 668 to 627 BCE, Ashurbanipal was not only a skilled military leader but also an intellectual with an insatiable thirst for learning. His library, discovered in the mid-19th century, contains thousands of clay tablets inscribed with cuneiform writing, covering a broad range of topics from religious texts to administrative documents, scientific knowledge, and historical records. This treasure trove of knowledge sheds light on the civilization of Mesopotamia and its profound contributions to human advancement.

Ashurbanipal’s reign is often remembered for its military conquests and the expansion of the Assyrian Empire, but equally important was his passion for learning. Unlike many kings of his time, Ashurbanipal was able to read and write—a remarkable feat in a society where literacy was typically the domain of priests and scribes. This intellectual prowess influenced his decision to gather the literary works of his empire and its neighbouring regions, assembling what is arguably the first systematically organized library in history.

Ashurbanipal’s education was rooted in the teachings of the temple, where he studied Sumerian and Akkadian, the two main languages used in Mesopotamia. His deep understanding of these languages allowed him to appreciate the breadth of knowledge contained in the ancient texts. This understanding spurred his desire to preserve, compile, and expand upon the wisdom of the past, a vision that would culminate in the creation of his royal library.

One of Ashurbanipal’s key motivations was his interest in divination texts, which he believed were crucial to maintaining his royal power. His library thus became a repository of rituals and incantations, reflecting the symbiotic relationship between knowledge and authority in ancient Mesopotamian culture.

Many tablets in his library contained a colophon—a “finishing touch,” similar to today’s title pages—containing a warning to library users to take good care of the materials. These early forms of passive-aggressive library signs were quite explicit:

- “He who fears Anu, Enlil and Ea shall return to the house of the master on the same day.”

- “He who fears Marduk and Serpanitum shall not entrust it to another. Cursed be all the gods of Babylon who entrust it to another!”

- “He who fears Anu and Antu will read the tablet and respect it.”

- “According to the order of Anu and Antu, the tablet must be in good condition.”

- “In the name of Nabu and Marduk, do not rub the text!”

- “He who breaks this tablet or puts it in water or rubs it until you do not recognize it and understand it, Ashur, Sin, Shamash, Adad and Ishtar, Bel, Nergal, Ishtar of Nineveh, Ishtar of Arabella, Ishtar. Bit Kidmuri, the gods of heaven and earth and the gods of Assyria, all will curse him that cannot be alleviated, terrible and merciless, his name will be blotted out and his flesh will be fed to the dogs!”

Modern library etiquette seems rather functional by comparison, doesn’t it?

The ruins of the Royal Library of Ashurbanipal were unearthed in the mid-19th century by archaeologist Austen Henry Layard. The majority of its contents were transported to the British Museum in London, where they continue to be studied and admired. Despite the plundering and subsequent mixing of the tablets with those from other sites, the library’s discovery remains a monumental achievement in the field of archaeology.

Layard’s assistant, Hormuzd Rassam, made a similar discovery three years later in the palace of King Ashurbanipal. However, due to the lack of proper documentation, the original contents of the two libraries are now almost impossible to reconstruct. Nevertheless, the surviving tablets offer invaluable insights into the intellectual and cultural landscape of ancient Mesopotamia.

The destruction of Nineveh in 612 BCE by a coalition of Babylonians, Scythians, and Medes marked the end of the Assyrian Empire. During the burning of the palace, the clay cuneiform tablets in Ashurbanipal’s library were partially baked, ironically preserving them for posterity. This unintended preservation through fire allowed future generations to access and study these ancient texts, ensuring that the wisdom of the past would not be entirely lost to the ravages of time.

On this ILD, as we reflect on the significance of reading and education, the story of the Royal Library of Ashurbanipal serves as a powerful reminder of the enduring human quest for knowledge. The library’s vast collection, the intellectual pursuits of its founder, and the subsequent discovery and preservation of its contents underscore the timeless value of literacy and learning.

In celebrating this day, let us honour the legacy of Ashurbanipal and his library, recognizing the vital role that libraries and literacy play in shaping our world. As we continue to explore and preserve the treasures of our past, we pave the way for future generations to build a more informed and enlightened society.

Wow! That’s incredible. India too has a rich history of knowledge preservation, from ancient Buddhist libraries in Nalanda to the magnificent Sarasvati Mahal Library. It’s fascinating to think about travellers like Fa-Hien and Hieun-Tsang visiting these treasure troves and carrying wisdom across continents. However, it’s sad that there are many historical libraries that have been lost to time and conflict.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re right, Nilanjana. Thanks.

LikeLike

Very informative

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks. Geeta.

LikeLike

First time I knew about this Royal library of Ashurbanipal . It’s a legacy . It’s name also interesting came from a name of a king well shared

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Priti.

LikeLiked by 1 person

💐

LikeLiked by 1 person

Nice, valuable content.

I guess, unfortunately in today’s time, the importance and number of libraries have shrunk in the country, so as even the basic inclination to grow/remain attached to the library culture.

I still remember, how much we used to love the DPL in our colonies, when we were in schools and colleges !

Nevertheless, my certain words above may be incorrect due to my limited knowledge on the subject.😒

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, and there used to be mobile libraries visiting us on particular days of the week and pre-determined time slots.

LikeLike

Nice information.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, sir.

LikeLike

Pingback: 30 Times Humans Destroyed Priceless Historical Objects - Back in Time Today