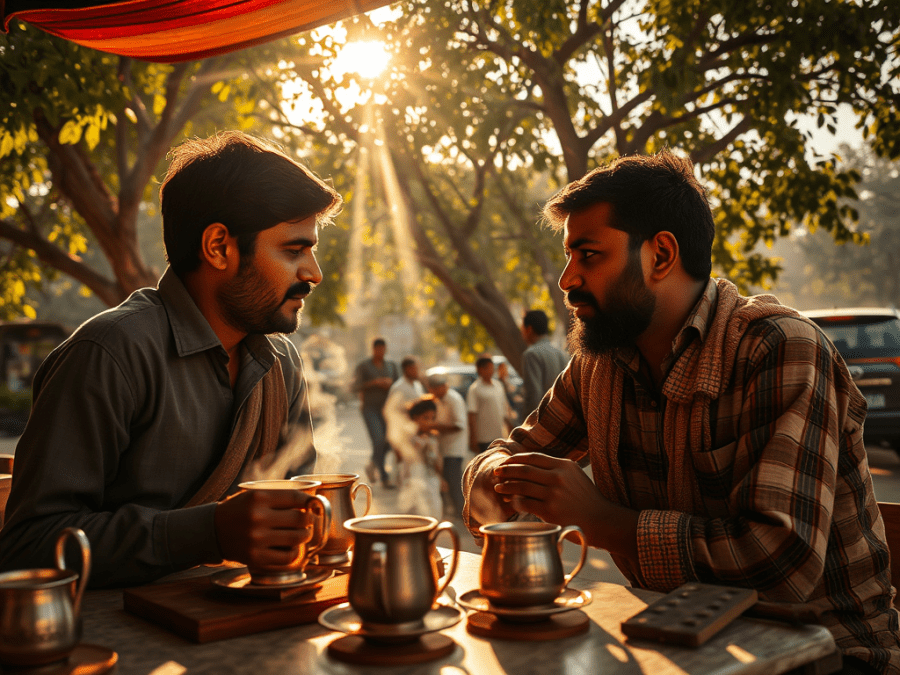

It’s a mild afternoon in Ranchi, the kind where time seems to slow just enough to let conversations stretch and stories linger. We’re at a quiet tea stall near Morabadi, steam curling up from earthen cups of chai, and as is often the case, our talk drifts first to the weather, then to local gossip, and finally to the many ways people speak across our corner of the world.

My friend, leaning back on the rickety bench, took a thoughtful sip and said, “You know, it’s strange how some of these so-called ‘dialects’ feel like they could stand on their own. Take Maithili in Madhubani, Bhojpuri in Chhapra, or Bangal bhasha in Barasat. You hear them, and you think—how are these just ‘variations’?

That question hung in the air, as warm and inviting as the chai in our hands. It was the spark of something deeper, a moment that made us question the neat little boxes we’d been taught to trust: “language” in one, official and respected; “dialect” in another, spirited but somehow less legitimate. It was like looking at a banyan tree, its sprawling roots dipping into the earth, some sprouting into trunks of their own—distinct, yet tethered to the same source. Could it be that the lines we draw between language and dialect are less about linguistics and more about who gets to decide what counts?

The Roots of Language: A Tale of Pride and Power

That afternoon, we began to unravel the question: what makes a language a language? Is it the grammar, the vocabulary, the way words roll off the tongue? Or is it something less tangible—something tied to power, to who speaks it, who writes it, and who gets to call it “official”?

In Bihar, the story of Maithili feels like a quiet triumph. This is a language with roots stretching back centuries, woven into the poetry of Vidyapati, a 14th-century bard whose verses of love and devotion still echo in the hearts of millions. Maithili is a language of philosophy, of song, of intricate literary traditions. Yet, for years, it lingered in the shadows, dismissed as a mere dialect until 2003, when it was finally recognised in the Eighth Schedule of the Indian Constitution. It was a victory, but one hard-won, a reminder that recognition often comes only after a long fight.

Then there’s Bhojpuri, a language that pulses with life across the Gangetic plains, Nepal, Mauritius, and even the Caribbean. With tens of millions of speakers and a thriving film industry, Bhojpuri is a cultural force—bold, vibrant, unapologetic. Yet it still waits for the kind of formal acknowledgement Maithili fought for, often labelled a dialect of Hindi despite its distinct identity. And what of Angika and Magahi, spoken with pride in the villages of Bihar? These are languages of oral epics and folk songs, yet in official documents, they’re often relegated to the margins, dismissed as “variants” of Hindi.

Cross into Bengal, and the linguistic landscape grows even more intricate. Bangla may reign as the dominant language, but within it lies a kaleidoscope of voices. There’s Bangal bhasha, spoken by those with roots in East Bengal, its cadence carrying the weight of migration and memory. Then there’s Sylheti, a tongue so distinct that some argue it deserves to be called a language in its own right. Sylheti thrives in homes and markets, but in formal settings, it often fades into the background, caught in a strange limbo between pride and invisibility. And don’t forget the regional flavours of Bangla spoken in Medinipur, Chattogram, Borishal, or Dinajpur—each with its own rhythm, its own soul.

In Uttar Pradesh, the story shifts again. Brajbhasha, once the language of devotional poetry sung in praise of Shri Krishna, now feels like a cherished heirloom, admired but rarely used. Bundeli, with its rugged charm, carries the spirit of Bundelkhand’s hills and forts. Both are often labelled dialects of Hindi, but listen closely, and you’ll hear vocabularies and idioms that defy any standardised mould. These are not just ways of speaking—they’re vessels of history, culture, and collective memory.

And here in Jharkhand, the languages of Sadri, Kurukh, Mundari, Ho, and Santhali weave a tapestry of their own. These are tongues of oral epics, ritual chants, and living traditions, yet they’re often dismissed as “tribal dialects.” But to those who speak them, they are the heartbeat of the community, the thread that ties generations to the land.

A River of Words: The Evolution of Language

Think of it like this: language evolution is a continuous process. As the sun began to dip behind the Sal trees, casting long shadows across the tea stall, we found ourselves marvelling at the fluidity of language. What we call “languages” today—Hindi, Bengali, Marathi—were once dialects of ancient tongues like Prakrit or Apabhraṃśa. And what we call “dialects” now—Brajbhasha, Sadri, Sylheti—might one day be recognised as languages in their own right, as communities assert their identities and carve out their place in the world. The labels we use are not set in stone; they’re snapshots of political history and power dynamics.

Take Hindi, for instance. Its story is one of convergence and choice. Born from Sanskrit, it evolved through Shauraseni Prakrit and Apabhraṃśa around the 7th or 8th century, initially known as Old Hindi. Over time, it absorbed influences from Persian and Arabic through interactions with Muslim rulers, and later, it was formalised under the British Raj as an official language alongside others.

But why did Khariboli, the dialect spoken around Delhi, become the foundation for Standard Modern Hindi? It wasn’t because it was inherently superior—it was because Delhi was a seat of power. Khariboli was the dialect closest to the throne, the one chosen to represent a vast and diverse linguistic family.

What becomes clear is that this isn’t just about grammar or phonetics. It’s about recognition. And recognition, more often than not, is tied to power. When Khariboli, the dialect around Delhi, was chosen as the foundation for Standard Hindi, it wasn’t necessarily because it was the most beautiful or expressive. It was probably chosen because it was closest to the seat of political authority.

It’s the same logic behind that often-quoted quip: “A language is a dialect with an army and a navy.” Funny, yes—but it rings with truth. What we call a “language” often depends on who gets to publish books in it, who gets airtime, and who gets textbooks written and printed in it. Recognition is rarely about linguistics alone—it’s about who holds the pen and the microphone.

Listening to the Stories Behind the Words

And this brings us to the heart of it all: When we reduce languages with millions of speakers, distinct traditions, and literary legacies to the label of “dialect,” we’re not just making a linguistic judgment. We’re making a political one. We’re deciding who gets to speak with authority, and who doesn’t.

To call Brijbhasha or Bhojpuri a dialect while elevating Khariboli to national status isn’t just a linguistic decision—it’s a political one. Much like saying Madhubani or Sohrai art is just a “folk style” and not “real” art misses the centuries of tradition, skill, and philosophy embedded in every brushstroke, calling a language with millions of speakers and a deep-rooted oral heritage a “dialect” does disservice to its richness.

The next time someone speaks in a way that seems unfamiliar, perhaps we’ll listen a little more carefully. Not just to the words, but to the story behind them. Every so-called dialect carries the imprint of migration, struggle, love, and survival. It is not a deviation from some imagined centre. It is the centre for someone, somewhere.

As we paid for our chai and stepped into the cooling evening, the world felt a little richer, a little louder with voices. Language, we agreed, is never just language. It’s memory. It’s identity. It’s resistance. And maybe, just maybe, it’s time we listened more closely—not just to the sounds, but to the lives they carry.

In the murmur of Maithili, the cadence of Brajbhasha, the pulse of Santhali, we hear the Ganga, the Mayurakshi, the Brahmaputra—rivers that flow without care for labels, nourishing the stories of those who live along their banks. And in their flow, we find a truth: the tongues we speak are as vast and vital as the waters that sustain us.

I think my grandmother used to say that the version of Hindi used changes every 20 miles. This is in the Khariboli centre of Meerut and Western UP in general.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s a fascinating observation about the rapid linguistic changes across short distances in India! While the “every 20 kilometers or so” idea, observed in many places, might be a generalization, it really highlights the incredible linguistic tapestry of the country. With over 1,600 languages belonging to so many different families like Indo-Aryan, Dravidian, and Tibeto-Burman, it’s no wonder that you see such vibrant regional variations in how people communicate. It truly makes language a living, breathing reflection of India’s diverse cultural landscape and rich history.

It’s also worth noting that geographical isolation due to natural barriers like mountains and rivers, historical migrations and invasions, and even the social structures of the past have all played a significant role in fostering this linguistic mosaic. The fact that different communities developed somewhat independently for long periods allowed these subtle but distinct variations to emerge and persist. It’s a testament to the deep roots and unique identities found across India.

LikeLike

What a beautifully written and insightful article! You’ve captured the richness and complexity of India’s linguistic landscape with remarkable depth. The way you question the arbitrary divide between “dialects” and “languages” is especially powerful—highlighting how regional tongues like Maithili, Bhojpuri, Brajbhasha, Bundeli, Sylheti, and Jharkhand’s tribal languages are not mere offshoots but cultural powerhouses with deep roots in literature, history, and everyday life.

Your analysis of how political power, rather than linguistic merit, shapes recognition—using Khariboli’s rise as a prime example—is both thought-provoking and important. The homage to languages like Maithili and Bhojpuri, and the evocative imagery of Bangla’s regional variations, shows how language breathes through people and places.

And the metaphor of languages as rivers flowing across boundaries—carrying memory, wisdom, and identity—is simply poetic. A deeply appreciative and enlightening read! 🙏🏽🙏🏽

LikeLike

Thanks, Dipen for your nice remarks and appreciations.

LikeLike