The year was 1852. The air in the Calcutta offices of the Great Trigonometrical Survey of India was thick with the oppressive humidity of a Bengal afternoon and the quiet arrogance of the British Raj. Files were stacked high, and the only sound was the scratching of pens—until it wasn’t.

A lean young Bengali man burst into the room, eyes blazing with the intensity of someone who had stared too long at numbers that reshaped the world. He was not reporting for duty. He was carrying history in his hands.

“Sir,” he is said to have declared, unable to contain himself, “I have discovered the highest mountain peak on Earth.”

That young man was Radhanath Sikdar. He had just completed the most complex mathematical calculation in the history of surveying, proving that a remote, unnamed peak known only in the Survey records as ‘Peak XV’ was the zenith of the world.

Yet, as with so many colonial-era breakthroughs, the glory was snatched away. The peak would be immortalised as Mount Everest, named after a British official who never even saw it. Radhanath Sikdar, the genius who crunched the numbers, was relegated to the dustbin of history—a casualty of British imperial bias and an appalling act of academic erasure.

The Herculean Task: Mapping an Empire

To understand the enormity of Radhanath’s achievement, we must first appreciate the scale of the Great Trigonometrical Survey (GTS) of India. Started in 1802, the GTS was a monumental undertaking designed to map the entire Indian subcontinent with scientific precision. It involved laying down a vast, interlocking network of triangles across thousands of miles, using massive, custom-built theodolites.

The goal of the GTS was not just geographical; it was geopolitical. The British needed to know exactly what they controlled.

By the 1840s, the focus had shifted to the icy, impenetrable wall of the Himalayas. The Kingdom of Nepal, fiercely independent, refused to allow British surveyors within its borders. This meant the peaks had to be measured from stations located hundreds of miles away in the plains of India, often over distances of 100 miles or more.

The Mathematical Nightmare

Nepal’s refusal to admit British surveyors forced the Survey to rely on distant observation points in the Indian plains—often more than 100 miles away. The mountains were visible, but unreachable. What followed was not mere geometry, but a brutal exercise in applied mathematics. The calculations had to account for a host of variable, confounding factors:

- The Curvature of the Earth: The peak’s true height needed correction for the spherical shape of the planet.

- Atmospheric Refraction: Light rays bend as they pass through layers of the atmosphere (refraction), causing the peak to appear higher or lower than it truly is.

- Temperature and Barometric Pressure: These continuously shifting variables affect the density of the air, which in turn influences refraction.

The complexity was staggering. The data collected from multiple observation points had to be meticulously processed using the most advanced logarithmic and trigonometric techniques available. Colonial science depended not only on instruments, but on human minds capable of taming chaos into certainty. These minds belonged to the “computers”—Indian mathematicians whose labour powered imperial knowledge while remaining largely invisible.

Among them, one stood unmatched.

The Genius of Radhanath Sikdar

Born in Calcutta’s Jorasanko Sikdar Para, Radhanath Sikdar was no mere clerk. He was an alumnus of the prestigious Hindu College (now Presidency University), where he was a star pupil of the firebrand teacher, Henry Louis Vivian Derozio. Sikdar was steeped in the liberal, rationalist philosophy of the Young Bengal movement.

This was not an education designed to produce obedient clerks. It produced sceptics, rationalists, and men who believed that authority must justify itself.

Sikdar’s mathematical ability soon became legend. When he joined the Survey in 1831, he already possessed a command over geodesy that rivalled—and often surpassed—that of his British superiors. Newton, Laplace, and advanced European trigonometry were his everyday tools.

The Human Computer Who Refined Science Itself

Sikdar’s greatest contribution was methodological. European scientists of the era struggled to reliably correct for atmospheric refraction. Sikdar developed a refined formula that integrated corrections for temperature, pressure, and refraction with unprecedented accuracy.

This was not clerical work. It was original scientific innovation.

Applying his method to streams of Himalayan data, Sikdar reached a conclusion that quietly redefined the world’s geography:

Peak XV stood at 29,000 feet—the highest point on Earth.

The Great Betrayal

The person who received this world-altering news was the Surveyor General, Andrew Waugh. Waugh was immediately faced with a choice: credit the unknown Bengali genius who had toiled in the Calcutta office or claim the discovery for the Empire.

To acknowledge Sikdar would mean admitting that the planet’s highest mountain had been identified through the genius of an Indian mathematician, a “Native” or kaala aadmi (dark man). In the racial logic of empire, this was intolerable.

Although Tibetans had long referred to the mountain as Chomolungma and the Nepalese as Sagarmatha, these indigenous names were not officially acknowledged by the British authorities at the time, since Tibet and Nepal were mostly inaccessible to foreigners.

In 1865, following the advice of Andrew Waugh, the British Surveyor General of India, the Royal Geographical Society officially designated the mountain as Mount Everest, in tribute to Sir George Everest, Waugh’s predecessor in the same position, who had neither seen the mountain nor been involved in the key measurements. Ironically, Sir George Everest himself was uneasy with this recognition, believing that significant geographical landmarks should keep their native names rather than be renamed after people.

Mount Everest was thus born—a name chosen not for its discoverer or measurer, but for its symbolic value as a white, Western tribute. The scientific community, though aware of the situation, offered little resistance. Science, when filtered through empire, often bends towards power.

The Politics of Two Feet

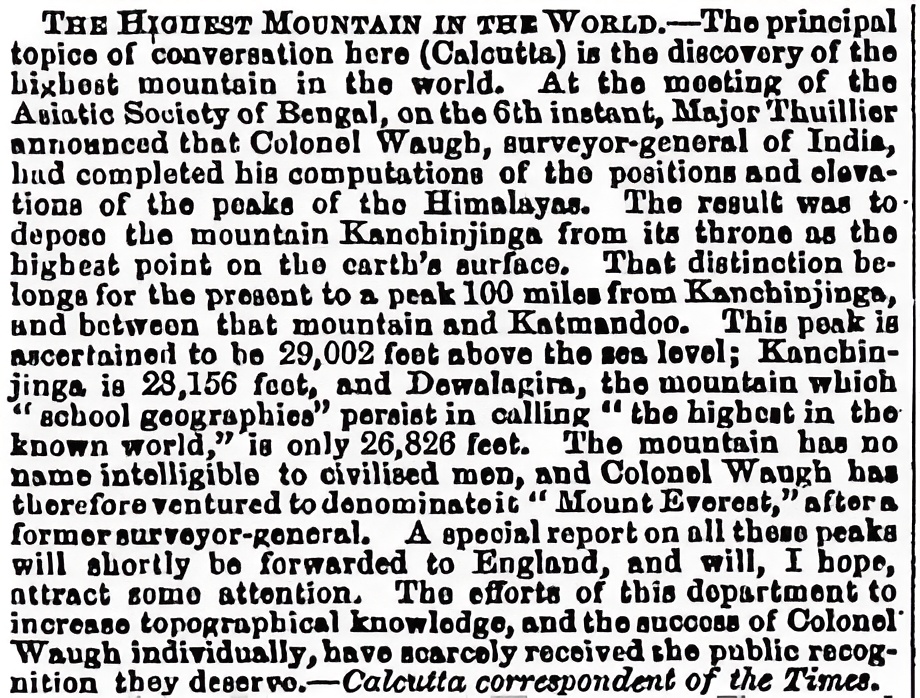

Sikdar’s calculated height—29,000 feet—was almost perfectly accurate. Yet Waugh altered it, adding two arbitrary feet to avoid the appearance of a suspiciously round number. This act of trivial, calculated dishonesty illustrates the extent of the conspiracy: not only was the credit stolen, but the accuracy of the original scientist was also subtly undermined and corrected by an administrator. This figure, 29,002 feet, stood as the official height for decades.

Modern Measurements

Modern measurements have refined Everest’s height by explicitly accounting for the constantly changing thickness of snow and ice at its summit—a factor nineteenth-century surveyors could not measure directly.

In December 2020, Nepal and China jointly announced the officially accepted height as 29,031.7 feet above mean sea level, a figure that includes the snow and ice cap. That Sikdar’s 1852 calculation of 29,000 feet came so remarkably close underscores the extraordinary accuracy of his work, achieved with nothing more than mathematics, patience, and human intellect.

Traditional geodetic surveying, while extraordinarily precise, is brutally demanding in Himalayan terrain. It must contend not only with distance and visibility, but also with subtle variations in Earth’s gravity, which affect the shape of the geoid—the true reference for mean sea level. Modern surveys therefore measure gravitational differences to refine this geoid, ensuring satellite-derived heights are correctly converted into elevation above sea level.

Today, high-precision GPS receivers are placed directly on Everest’s summit, calculating its height relative to the Earth’s centre with centimetre-level accuracy—a triumph of technology built upon the foundations laid by earlier geodesists like Sikdar.

Resistance Beyond Numbers

Sikdar’s refusal to bow before authority extended beyond science. In 1843, he clashed directly with Magistrate Vansittart, who habitually forced Survey employees to perform personal tasks and administered floggings. Radhanath, seeing this abuse, refused to stay silent. He took his protest to the English court, a brave and dangerous move for an Indian employee at the time.

He was fined 200 rupees for his dissent but emerged victorious in spirit. As a Derozian, he possessed an unshakeable sense of justice, famously declaring that he would never bow his head to any man.

This was heritage of a different kind: moral courage forged in an age of humiliation.

A Forgotten Hero

Though Sikdar rose to become Chief Computer of the Survey, recognition never followed. He lived unmarried, devoted entirely to science and thought. European scholars acknowledged his brilliance; British official histories largely ignored it.

While the German Philosophical Society eventually acknowledged his geodetic brilliance, official British records largely ignored his contributions. He passed away quietly in a garden house in Chandannagar in 1870, a great mind sinking into obscurity.

Remembering Peak XV

Today, Mount Everest stands as the ultimate symbol of natural grandeur. Yet its name conceals a deeper story—one of intellectual extraction and selective memory. Beneath the ice and snow lies a deeper truth, a story of the logarithmic genius of an uncompromising Bengali mathematician.

At Indrosphere, remembering Radhanath Sikdar is not merely historical correction. It is an act of heritage reclamation—a reminder that science does not exist outside power, and that empires often rise on the backs of forgotten minds.

Peak XV still stands, a silent monument to the intellectual theft and the forgotten glory of Radhanath Sikdar.

I’d love to hear from you! Please leave any questions, comments, or insights in the comments section below.

That is a wonderful appreciation of Radhanath Sikdar!

The depth and clarity with which this narrative is presented are a testament to a formidable capacity for historical synthesis and evocative writing. It is not enough merely to possess the facts; a truly compelling historical account requires the skill to weave together diverse threads—geodesy, colonial politics, philosophy, and personal biography—into a seamless and emotionally resonant tapestry. Your writing achieves this with remarkable effectiveness, making the oppressive humidity of the Calcutta office and the blazing intensity in Sikdar’s eyes palpable to the reader.

Furthermore, the knowledge demonstrated here is not simply broad, but incisively analytical. The piece deftly handles complex scientific concepts, such as the corrections for atmospheric refraction and the subtlety of the geoid, ensuring they are comprehensible without sacrificing precision. Beyond the technical, the commentary recognizes the political mechanics of the era—the “racial logic of empire” that deemed an Indian genius “intolerable” for receiving credit. This nuanced understanding of power dynamics and academic erasure transforms the account from a mere biography into a powerful lesson in global intellectual history. The appreciation is due not just to Sikdar, but to your ability to articulate the profound injustice, making the story of Peak XV not just an anecdote about measurement, but a searing critique of intellectual extraction. To resurrect such a complex figure, ensuring his moral courage and multidisciplinary “neck” are equally celebrated alongside his mathematical zenith, speaks volumes about the quality and rigor of your historical knowledge.🙏🏽🙏🏽

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much for this generous and deeply perceptive response. Your reading captures exactly what I hoped to convey—that Radhanath Sikdar’s story is not merely one of scientific brilliance, but of intellect constrained by empire and dignity asserted through reason. I am especially grateful for your recognition of the attempt to balance technical precision with historical and moral context. To have the injustice, the science, and the human courage resonate with a reader as clearly as you describe is truly humbling. 🙏🏽

LikeLike

Absolutely! It’s infuriating how someone of Radhanath Sikdar’s brilliance could be sidelined like that. His work literally reshaped the world’s understanding of geography, yet colonial narratives conveniently ignored his contribution. Remembering and honoring him now is the least we can do. Truly a hero who deserves far more recognition. 🙏🔥Nice post, Indrajit.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! 🙏 I’m glad it resonated with you. Stories like Sikdar’s remind us how much history can overlook extraordinary minds, and why it’s so important to revisit and celebrate them. His courage and brilliance continue to inspire—truly a legacy worth honoring. 🔥

LikeLike

Very informative post upholding forgotten history.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks 🙏

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good that you have reminded the world about this genius.

India has many more unsung heroes than those who are considered ‘official heroes’.

And this is one of the greatest tragedies of India.

Ever since the days of invasions, our history has been written by someone else.

And it is only now, that the truth is gradually coming out.

As they say “Until the lion learns to write, every story will glorify the hunter”.

Keep it up my friend, expose the hunters as much as you can.

My best wishes are always with you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much for the kind words and the well wishes. You hit the nail on the head—the quote about the lion and the hunter is incredibly fitting here. For too long, these narratives have been one-sided, and it’s a privilege to help tip the scales by highlighting the brilliance that was tucked away in the margins of history. There are so many more stories to tell, and I’m glad to have you along for the journey.

LikeLike

A brilliant post !. I thoroughly enjoyed reading this fascinating piece of history about Mr. Sikdar. As someone living in Dehradun, I have often come across fleeting mentions of him, but this was the 1st time I read in detail about this genius and his work.

Your writing style is powerful and the words flow like a river stream, unhindered and effortless. I look forward to reading more of your posts.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much for your kind words. I’m glad the post helped shed deeper light on Mr. Sikdar’s life and work, especially since his name is so often mentioned only in passing. Your appreciation of the writing truly means a lot and encourages me to keep sharing such stories. I’m delighted you enjoyed it and hope you’ll continue reading more.

LikeLiked by 1 person