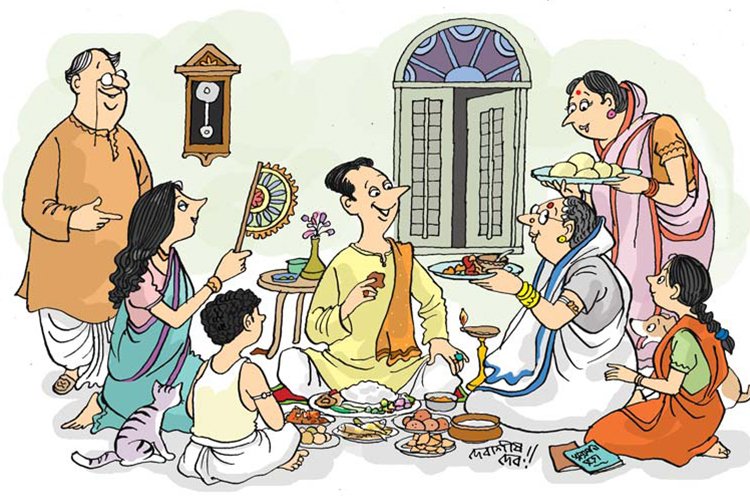

In the kaleidoscope of Bengali traditions, few festivals embody familial warmth and affection quite like Jamai Shoshthi. It is that time of the year when a mother-in-law showers her son-in-law—the jamai—with love, blessings, and a royal feast, celebrating not just his presence in the family, but the bond that unites two generations through the daughter’s marriage.

Falling on the sixth day (Shoshthi) of the waxing moon in the month of Jyestha (around May or June), Jamai Shoshthi is more than just a social ritual—it’s a symphony of love, gratitude, and culinary indulgence. The festival reflects the Bengali way of life, where relationships are nurtured with warmth, laughter, and, of course, good food.

“In Bengal, love is best served on a plate — warm, generous, and draped in nostalgia.”

The Heart of a Bengali Celebration

My earliest memories of Jamai Shoshthi are from my childhood—of a bustling household alive with excitement and the comforting aroma of food simmering in brass pots. The courtyard would echo with chatter and laughter as my mother and aunts competed good-naturedly over who could outdo the other in culinary finesse.

For Bengalis, the jamai is no ordinary guest. The morning begins with a simple ritual—the mother-in-law ties a sacred thread on the son-in-law’s wrist, blessing him with good health and prosperity. But the real celebration unfolds at the dining table, for as the saying goes, “Baro mashe tero parbon”—thirteen festivals in twelve months—and every one of them is an occasion to feast!

“In every Bengali kitchen, love simmers with the dal, the fish, and the laughter of generations.”

The Royal Feast

A Jamai Shoshthi meal is a gastronomic spectacle—an opulent spread that mirrors Bengal’s culinary richness. There’s shukto, the bittersweet vegetable medley that opens the appetite; macher kalia and bhaapa ilish, the beloved Hilsa prepared in all its glory; kosha mangsho, the rich, slow-cooked mutton curry; chingri malai curry, prawns in creamy coconut gravy; and, of course, a finale of mishti doi, rosogolla, and sandesh.

Each dish is lovingly prepared and served on banana leaves, simple yet symbolic of purity and celebration. As the family gathers around, laughter fills the air and stories flow as freely as the ghee on the rice. Every morsel carries affection, every serving a gesture of belonging.

When Tradition Took an Unexpected Turn

My own first Jamai Shoshthi as a newlywed, however, didn’t unfold quite as expected. What began with joy and anticipation soon turned into an unforeseen test of emotion.

As the day progressed and the feast neared completion, my mother-in-law—who had been managing everything with her characteristic enthusiasm—suddenly fell ill. The evening that was meant to echo with laughter turned into one filled with concern. We spent that night in the hospital, waiting and praying for her recovery.

I stayed on for a few days, helping where I could. The festive mood had dissipated, replaced by a quiet sense of togetherness born of care and worry. That year, Jamai Shoshthi became less about feasting and more about family—the kind of love that stands steady in the face of uncertainty.

Perhaps that’s why, in the years that followed, I never visited my in-laws on Jamai Shoshthi again. No one insisted, and maybe that was their way of acknowledging that some memories, though precious, are best left untouched.

Reflections Beyond Rituals

Looking back, I often think of that day—not with regret, but with gratitude. It taught me that festivals are not merely about rituals or perfect celebrations. They’re about the people who make them meaningful, the bonds that endure through joy and difficulty alike.

As times change, Jamai Shoshthi, too, evolves. The elaborate home-cooked spreads may now be replaced by restaurant outings, and rituals may be simplified. Yet, the essence remains the same—a celebration of love, laughter, and belonging.

The True Feast

Today, when I think of Jamai Shoshthi, it’s not just the memory of Hilsa and sweets that lingers—it’s the reminder that love is expressed not only in laughter and indulgence but also in quiet resilience and shared moments of care.

“Festivals fade, but the feelings they awaken remain etched in the heart.”

So, if you ever find yourself in a Bengali home on Jamai Shoshthi, enjoy the feast, the laughter, and the warmth that fills the air. But know this—the real celebration lies beyond the food and festivities. It lives in the emotions that bind us, the stories that we pass on, and the moments that, though imperfect, remain etched in the heart.

সুতৃপ্তি! भोजनं स्वादिष्टमस्तु! Bon appétit!

Sons-in-Law Get the Star Treatment: Global Traditions

While Jamai Shasthi in Bengal is famous for showering sons-in-law with sweets, sumptuous meals, and a touch of royal treatment, similar traditions exist around the world. In China, during the Lunar New Year and in ethnic communities like the Dong and Miao, sons-in-law are welcomed with lavish meals and gifts, ensuring they feel right at home.

In Korea, festivals such as Chuseok and Seollal see sons-in-law being served first at feasts and given thoughtful presents—a culinary and cultural nod to their importance. Even in rural Eastern Europe and the Balkans, the arrival of a new son-in-law is marked with hearty feasts, dances, and symbolic gifts.

“Whether it’s Bengali sweets, Chinese dumplings, or Korean festive feasts, one thing is universal: a pampered son-in-law is a happy son-in-law!”

Epilogue

Through the gentle weave of humour, memory, and flavour, the timeless Bengali festival of Jamai Shoshthi unfolds as more than a ritual—it becomes a song of love, kinship, and life’s tender unpredictability. It whispers that true celebration is not found in the perfection of customs, but in the imperfect, shared moments that linger in our hearts—the laughter around a meal, the warmth of togetherness, and the quiet ties that bind generations across time.

Because in every Bengali home, love still tastes like home-cooked memories.

hahahaha have fun & enjoy the attention of Sasur Badi Choudhary Saab !

Though there is no such DAY in other communities in India but jamaai is a raja nevertheless everywhere & everyday in the eyes of sasur bad.

While on the subject I guess you will enjoy this story – सास का घर –

http://jogharshwardhan.blogspot.com/2014/08/blog-post_12.html

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very true. An Indian jamaai is always a Raja in his sasur badi irrespective of his age or age of his marriage. 🙂

Hahaha, nice story. Very true, why will he stay at sasural if he has to work there?

Swarnkar saab was a great boss. I admire him a lot, and I was lucky to work under him.

LikeLike

Yes he was a wonderful man.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ha ha good article. Hope you had been to shasur Bari and enjoyed the treatments with shala shalis!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Anil. Unfortunately, I am very far away from my shoshur bari and so couldn’t enjoy the “জামাই আদর”. 😦

LikeLiked by 1 person

Bad luck! এক বছরে দীর্ঘ প্রতিক্ষা ! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

hahaha! 🙂

LikeLike

Lived in bengal for four years, appreciate the sentiments in this post 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Nitin. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are welcome Indrajit 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

My mom is a big fan of her son-in-law. I’ll have to tell her about this.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hahaha! And her son-in-law will be all the more happy to get pampered. 🙂

Thanks for dropping by.

LikeLike

The jamais wait for the whole year to be pampered on this day 😀 A unique celebration it is. These days, I’ve observed posts here and there against the ritual, from the feminist wing… 😛

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes quite true, Maniparna. This festival serves the purpose of bringing the son-in-law much closer to the family. It gives an opportunity to invite the married daughters to their paternal home. It is a completely family festival which brings together other family members as well. I don’t see any cause for feminists to protest against this tradition. A holistic view should be taken instead of looking at the things with tinted glasses, every time. Modernisation doesn’t mean to shun every age-old practices and traditions.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hmmm… I agree… 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow! this is so interesting. Thanks for sharing!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Rashmi. 🙂

LikeLike

WHoa! the JamaiBabus are really Rajas in Bengal..hmm! Interesting read!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Bushra. 🙂

LikeLike

Sentiments are good. 😀 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Somali 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

Pingback: Sorshe Ilish | Hilsa in Mustard Gravy – INDROSPHERE

nice post sir,

very well narrated about JAMAI RAJA..

thanks for sharing..

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, sir.

LikeLike

Excellent write up..new learning about Chinese tradition one

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks.

LikeLike

Happy Jamai Sosthi, Indrajit. I hope this wish is more appropriate for Judhajit. 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Nilanjana.

LikeLike

😀👍

LikeLike