There are places where history does not lie dormant. It breathes. It murmurs beneath broken bricks and wind-worn walls, waiting for someone to listen. Babylon is one such place. And within its sacred heart, close to the Processional Way and the once-resplendent Ishtar Gate, lies the story of a goddess whose name time has tried—but failed—to erase.

Her name was Ninmakh.

In the cradle of civilisation, amidst the fertile alluvium of Mesopotamia, where the Tigris and Euphrates first taught humanity how to dream in clay, Ninmakh emerged as the Great Mother. She was known by many names—Ninmah, Ninhursag, Mami, Nintu—each name carrying a different shade of her vast, life-giving presence. To the Sumerians, she was not merely divine; she was elemental. Healing flowed from her hands, fertility from her womb, and creation itself from her breath.

She stood among the seven great deities of Sumer, consort to Enki, god of water and wisdom. Where Enki brought knowledge and the sweet waters of the deep, Ninmakh shaped life—literally—moulding humanity from clay, infusing form with spirit. Creation, in Sumerian thought, was never accidental. It was craftsmanship. And Ninmakh was its master artisan.

She was often depicted as a maternal figure, crowned with a horned headdress, draped in a long flowing robe—a visual language of authority, nurture, and cosmic order. Women in labour whispered her name. The injured and ill invoked her protection. She was the goddess who restored what was broken, whether body, land, or soul.

A Temple Raised Layer by Layer, Like Memory

Babylon honoured her with a temple—not a fleeting shrine, but a structure rebuilt again and again across centuries, as if each generation felt compelled to lift her sanctuary closer to the heavens.

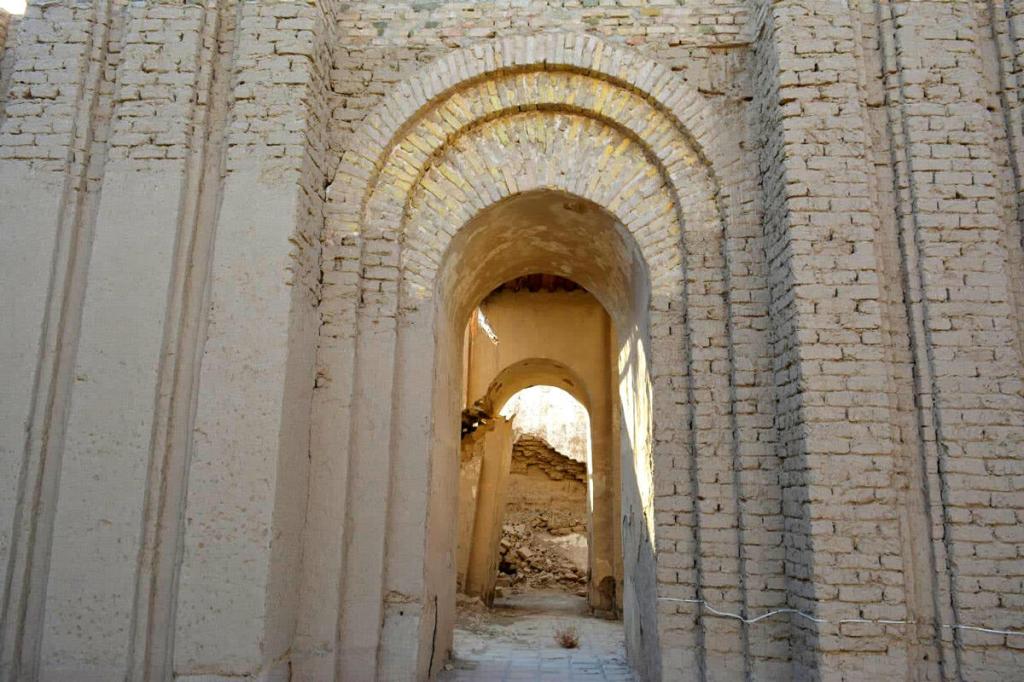

The Temple of Ninmakh, first excavated by the Koldewey Expedition between 1899 and 1914 and later re-excavated by Iraqi archaeologists, revealed a remarkable truth: every reconstruction rose several metres above the last. Walls were raised, floors re-laid, sacred spaces re-imagined—yet earlier walls survived beneath, preserved by layers of lime plaster and reverence.

This was no ordinary temple. Enclosed by a protective wall, it functioned not only as a religious sanctuary but as a cultural and civic nucleus. Within its confines, rituals were performed, prayers murmured, and matters of importance discussed. The sacred and the secular, inseparable in Mesopotamian life, flowed together here.

The temple’s central courtyard, open to the sky, held a holy well. Women drew water from it for ritual bathing and purification—a quiet echo of Ninmakh’s enduring role as guardian of birth, renewal, and continuity. Sacred wells like this dotted Babylon’s ritual landscape, mirroring the life-giving waters of the Euphrates itself.

The inner sanctum, however, was reserved exclusively for women. Here, young women prayed for good marriages; married women prayed for children. Men remained outside. Some mysteries, Babylon understood, belonged only to those who carried life within them.

Empires Rise, Stones Remain

The temple was rebuilt during the reigns of Esarhaddon, Assurbanipal, and Nebuchadnezzar II in the sixth century BCE. Yet archaeology tells a deeper story. Its structure reveals multiple rebuilding phases extending well beyond the Neo-Babylonian era. The ground plan shifted. Pavements once attributed to Nebuchadnezzar were later dated to the Parthian period. The temple endured, adapting and surviving long after empires fell.

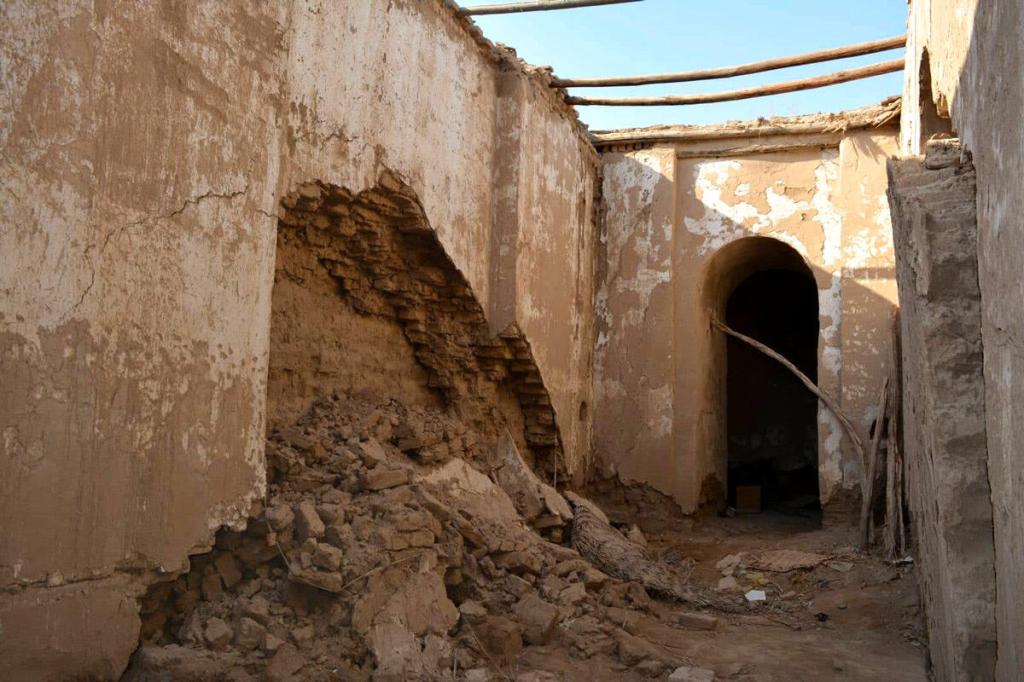

Today, it stands in poor condition—weathered by wind and rain, undermined by shifting river courses, rising groundwater, mineral salts, and centuries of neglect. These stones are not merely ruins; they are chapters of human memory, pleading for restoration before silence finally claims them.

The Mother in Myth

In myth, Ninmakh’s presence is vast and intimate all at once.

She was called “the true and great lady of heaven”, a title perhaps born of her association with mountains—the source of rivers, clouds, and sustenance. Sumerian kings were said to be “nourished by Ninhursag’s milk,” a poetic allusion to the life-giving waters flowing from the highlands into the plains.

Her son Ninurta, god of war and hunting, renamed her Ninhursag—Lady of the Mountain—after defeating the demon Asag and piling the corpses of stone monsters into the first mountains. Victory, in a rare act of filial humility, was gifted back to the mother.

In the Akkadian Atrahasis Epic (18th century BCE), she appears as Mami, the womb-goddess. Humans are fashioned from clay mixed with the flesh and blood of a slain god, born after ten months like any mortal child. Creation here is neither effortless nor clean—it is sacrificial, deliberate, and deeply human.

Another myth places Ninmakh alongside Anu, conceived together in the oceanic womb of the primordial goddess Nammu. Sky and earth entwined within the primeval sea, before separation, before order—before history.

Yet her story also bears the mark of loss. In the myth of Enki and Ninmah, Ninmakh begins as Enki’s equal. By the end, she is diminished. Scholars note that this myth may reflect a broader historical shift during the reign of Hammurabi, when female deities—and women—were gradually eclipsed by male authority. Even goddesses were not immune to patriarchy.

Listening to the Echoes

Standing amidst the ruins of Ninmakh’s temple, one feels the fragile boundary between myth and memory dissolve. This is not a place of spectacle. It is a place of listening.

The goddess no longer answers prayers, but her legacy endures—in every story of creation shaped by care, in every act of healing, in every reverence for the feminine principle that sustains life.

To visit this sacred site is to acknowledge that civilisation did not begin with conquest alone, but with birth, nurture, and craftsmanship. In Ninmakh’s story, Babylon speaks not only of gods and kings, but of women, water, earth, and the quiet power that holds worlds together.

In the ruins of her temple, the Mother of Gods still whispers—if we are willing to hear.

Wow! Nice post with lots of history and research. These mythologies give an idea about the culture and thinking of ancient people.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, Nilanjana.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is fascinating how every God or Goddess that we know of can be linked back to the Sumerian era.

Great post loved reading it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Zita. Earliest available recorded history is of Sumerian era. Rest all are in legends and mythologies until the world comes to know of some facts, artefacts, ruins belonging to civilisations prior to the Sumerians.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very informative, interesting and intriguing. It is eminently possible the characters (read god) across the globe that we dismiss as mythology actually existed. And if so, then a sinister conspiracy was hatched to burry the golden past without explaining how those massive structures were erected that lived to tell us something about those times.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, Aro. You may be right. Clay tablet 1 of the Atrahasis (18th century BCE) begins after the creation of the world but before the appearance of human beings: “When the gods, instead of man did the work, bore the loads. The god’s load was too great, the work too hard, the trouble too much.” The elder gods made the younger gods do all the work on the earth and, after digging the beds for the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, the young gods finally rebel. Enki suggests the immortals create something new, human beings, who will do the work instead of the gods. One of the gods, We-Ilu (also known as Ilawela) known as “a god who has sense” offers himself as a sacrifice to this endeavour and is killed. The mother Goddess, Ninmakh adds his flesh, blood and intelligence to clay and creates seven male and seven female human beings. You may read about the Atrahasis Epic and may find similarities with the Hindu mythologies, as well as the Genesis and mythologies of other tribes.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wonderfully researched. A comparison of the cosmogonical myths of different countries and culture indicates that they stand on a universal fact.

A very informative and intriguing article. Thanks for sharing… 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, Maniparna.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Informative, well researched Babylonian civilization just hrd about it. Lovely post. 👍👍

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Nitin.

LikeLike

This is so interesting, especially when you come, as I do, from a culture that only acknowledges a male god and has only male priests.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, goddesses lost their importance with the rise of patriarchy in the society, except at some places. Among Hindus, Goddess is worshipped by a large number of followers.

LikeLike

I love posts like these. They give me metaphorical materials, the meanings of which I can later interpret. I especially like the story of the mother goddess Ninmakh and son Ninurta, with the mountain metaphor included. These ancient stories contain important hidden knowledge. Great research and photos by the author. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Ranilo.

LikeLike