In Epicurean Enigma, I often explore how food becomes a mirror of civilization — a reflection of our evolution, rituals, and imagination. Every grain, spice, or simmering pot carries a story older than memory itself. Among these timeless tales, few are as fascinating as the world’s very first cookbook — born not from parchment or print, but from clay tablets in Ancient Mesopotamia, the land between the Tigris and Euphrates, now modern-day Iraq.

The Cradle of Culinary Civilisation

Food has always been much more than sustenance — it is memory, ritual, and identity. From the first sparks of fire-lit cooking to the fragrant kitchens of modern homes, humanity’s journey can be told through what it eats. Long before celebrity chefs and glossy cookbooks, the earliest known recipes were etched on clay tablets in the land once called Mesopotamia — the cradle of civilisation.

Between 4000 BCE and 539 BCE, the Mesopotamians thrived between the life-giving rivers. Blessed with fertile soil, they cultivated barley, wheat, and lentils, and raised sheep, goats, and cattle. This early society’s sophistication extended beyond trade and governance — into the art of flavour itself.

The World’s Oldest Cookbook

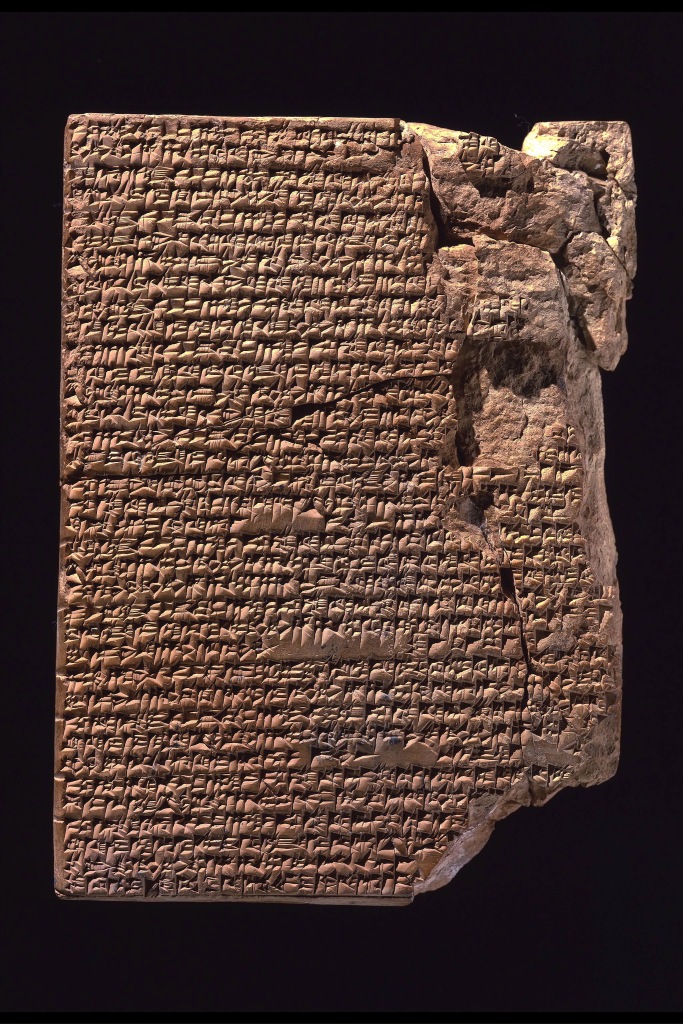

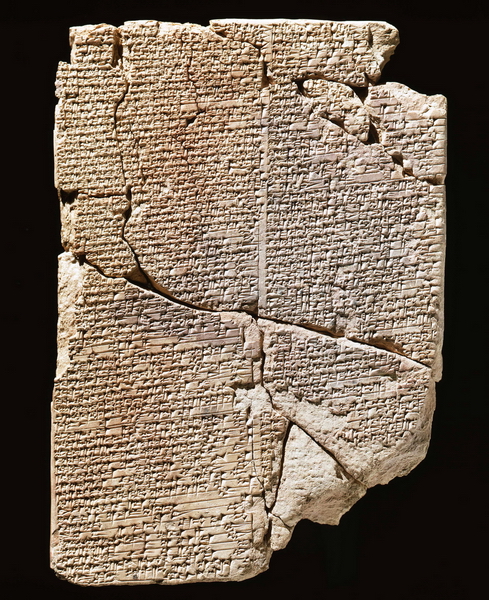

The oldest known cookbook, dating back to around 1700 BCE, survives on three fragile Babylonian cuneiform tablets, now preserved in the Yale Babylonian Collection. These cracked tablets, inscribed by what might have been the world’s earliest master chefs, list recipes for stews, soups, breads, and beverages — including beer and wine. Remarkably, some of these dishes echo through time, resembling today’s Iraqi lamb stews fragrant with onion, garlic, and coriander.

The recipes don’t include measurements or cooking times — they were meant for professionals who already knew their craft. One tablet, YBC 4644, records 25 recipes for stews — 21 with meat and 4 with vegetables. Ingredients were to be added in sequence, simmered slowly in covered pots — a timeless technique still central to Iraqi cuisine, where dishes like Pacha trace their lineage back to these ancient instructions.

Flavours of an Ancient Kitchen

The Mesopotamians loved their flavors. Their kitchens pulsed with the scent of cumin, cardamom, saffron, and cinnamon, balanced with fresh herbs like mint, parsley, and coriander. Stews were thickened with grains, butter, beer, or even animal blood, yielding deep, complex flavors.

They relished meats — lamb, kid, fowl, stag, and gazelle — and supplemented their diet with fish, shellfish, and turtle. Fruits such as dates, figs, apples, pomegranates, and grapes were staples, as were bulbs, truffles, and mushrooms gathered from the fertile plains.

It was in Sumer, around 4000 BCE, that the art of stuffing minced meat into animal intestines — sausages — was born, a culinary invention that travelled across time and continents.

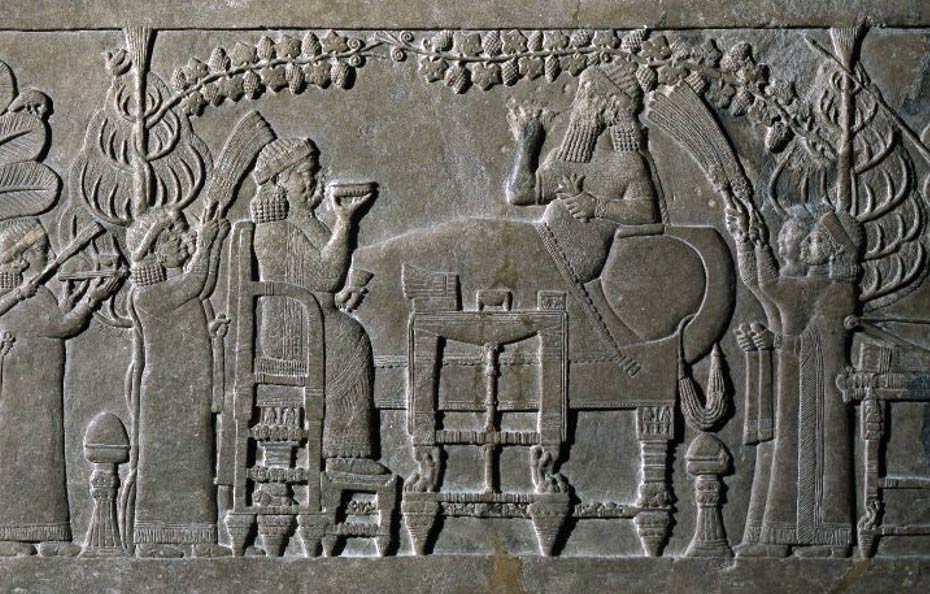

Feasts Fit for Kings

These elaborate recipes were not for the common household. They were the haute cuisine of their time — prepared for royal courts, temples, and great banquets. One legendary record describes a feast hosted by the Assyrian King Ashurnasirpal II in the 9th century BCE, where over 69,000 guests dined for ten days. They consumed 25,000 lambs and sheep, 500 gazelles, 30,000 birds, 10,000 loaves of bread, and rivers of wine and beer — a spectacle of abundance and devotion.

Food in Mesopotamia was sacred — a bridge between the earthly and divine. Many recipes were tied to festivals and offerings to gods, underscoring how the act of cooking intertwined with worship and celebration.

Legacy of the First Chefs

These cuneiform cookbooks reveal not only what ancient Mesopotamians ate but also how they lived, celebrated, and perceived the world. Their stews simmered with meaning — of community, of ritual, of joy. They remind us that the impulse to gather, to share, and to savour transcends time.

As we explore the rich culinary heritage of modern Iraq — from its aromatic rice dishes to slow-cooked stews — we taste the echoes of those early kitchens. The world’s first recipes, born from clay and fire, continue to season our understanding of culture and continuity.

In the story of civilization, Mesopotamia didn’t just invent writing and the wheel — it wrote the first cookbook. And through it, we glimpse how humanity first learned to transform survival into art.

Nice post. So people mainly used to eat stew!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Nilanjana.

LikeLike

everyone with good sense still mainly eats stew

LikeLiked by 1 person

Quite true. Thanks for dropping by.

LikeLike

I don’t think I have the guts (literally) to have Pache!!!🤪😜

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, it’s not for everyone. You need to be a bit adventurous in eating.

LikeLike

I would love to taste and eat an actual food prepared using one of those Mesopotamian recipes from thousands of years ago. That would be a genuine ancient experience.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Absolutely. But, I wonder whether the same experience is possible. There are some dishes still available e.g. Pache, Masgouf dating back to that era, but there have been some modifications in recipe or the cuisine over the period.

LikeLike