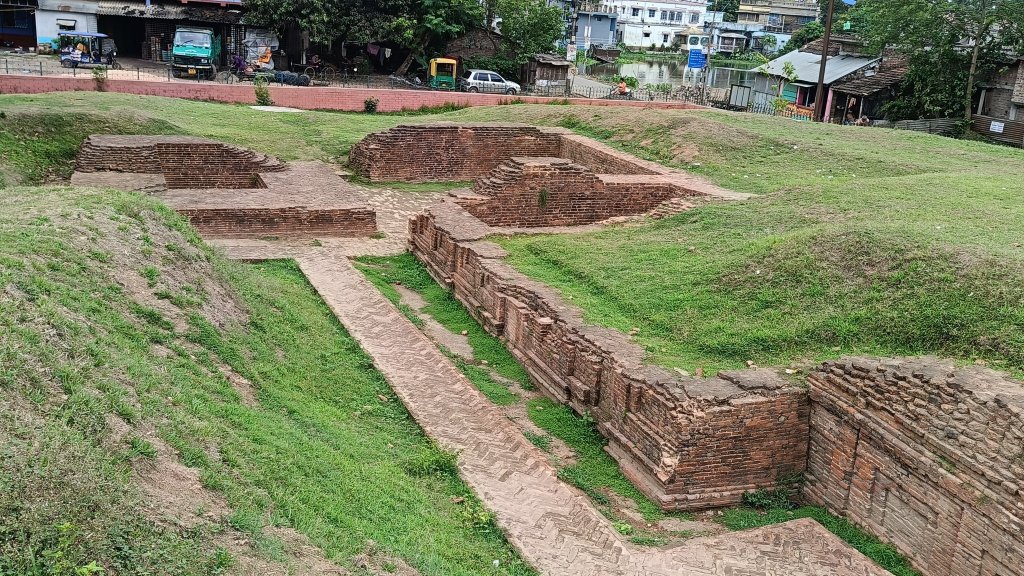

As I stood on the edge of the vast, green expanse of Chandraketugarh, just 35 kilometres northeast of Kolkata, the humid West Bengal air seemed to hum with whispers of a forgotten world. The Bidyadhari River flowed quietly nearby, its gentle ripples a reminder of the lifeblood that once sustained a thriving civilisation here. Surrounded by fields that stretched endlessly under the golden sun, I felt like I was stepping into a storybook, one where myth and history entwined, beckoning me to uncover the secrets of an ancient city lost to time. Chandraketugarh is no ordinary archaeological site—it’s a portal to a past that pulses with life, a place where the echoes of a vibrant, cosmopolitan society still linger in the terracotta figurines and crumbling walls.

A Personal Pilgrimage to the Past

My journey to Chandraketugarh began with a spark of curiosity, ignited by tales of a city older than memory itself. I’d heard whispers of this enigmatic place—stories of a port city that once connected India to the far reaches of the ancient world, from the Mediterranean to Southeast Asia. As a lover of history, I couldn’t resist the pull of a site that promised to bridge the gap between the world I knew and one that existed centuries before my time. The drive from Kolkata was short but transformative, trading the city’s chaotic energy for the serene, almost sacred quiet of the countryside. When I arrived, the sprawling ruins stretched before me, a silent testament to a civilisation that had flourished and faded long before my ancestors walked this land.

The Rise and Fall of a Forgotten Metropolis

Chandraketugarh’s story begins in the 4th century BCE, during a time when empires were born and trade routes crisscrossed the ancient world. This was no mere village—it was a bustling urban centre, a port city strategically perched along the Bidyadhari River, its waters carrying ships laden with goods to and from distant lands. From Persia to Rome, from Southeast Asia to the Gangetic plains, Chandraketugarh was a crossroads of cultures, a melting pot where ideas, art, and commerce thrived. Its massive walls, some still visible today, encircled a city of temples, stupas, monasteries, and homes, all teeming with life.

Historians believe Chandraketugarh may have been part of the ancient kingdom of Vanga, possibly even its capital, Gangaridai, mentioned in the writings of Greek geographer Ptolemy and diplomat Megasthenes. The name “Chandraketu,” tied to the site, bears a curious resemblance to “Sandrokrottos,” a figure in Greek texts often linked to the Mauryan emperor Chandragupta.

Could this city have been a linchpin in the ancient world, its ports welcoming traders from Rome and its markets buzzing with the exchange of spices, textiles, and ideas? The thought sent shivers down my spine as I wandered through the ruins, imagining the vibrant life that once animated these now-silent mounds.

Over the centuries, Chandraketugarh’s fortunes waxed and waned. It thrived through the pre-Mauryan era, flourished under the Mauryas, and continued to shine through the Gupta and Pala-Sena periods. But like so many great cities, it eventually faded into obscurity, buried beneath layers of earth and time. By the time the modern world rediscovered it, Chandraketugarh was little more than a whisper in the fields of Bengal.

The Terracotta Tales of a Lost World

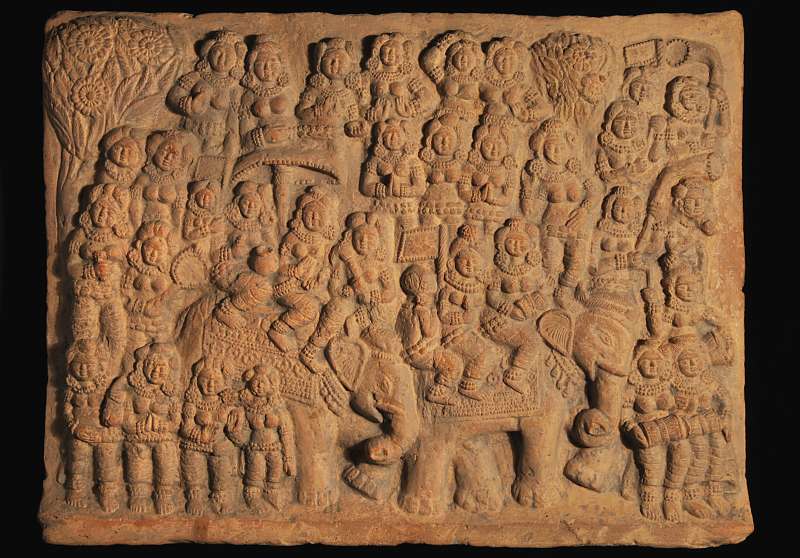

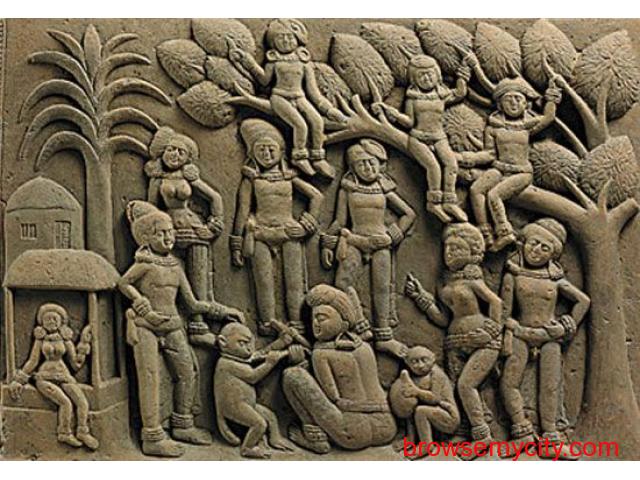

As I explored the site, my eyes were drawn to the terracotta sculptures that are Chandraketugarh’s most enduring legacy. These delicate, intricately crafted pieces are more than artefacts—they’re storytellers, each one capturing a moment in the lives of the people who lived here over two millennia ago. I stood in awe before a figurine of a fertility goddess, her form radiating strength and grace, her multi-armed silhouette wielding weapons in a dance of divine power. Another depicted a Proto-Durga, triumphantly slaying a demon, her image a precursor to the fierce goddess worshipped across Bengal today. These weren’t just sculptures; they were windows into a spiritual world where deities and mortals coexisted.

But it wasn’t just the divine that these terracottas immortalised. Some plaques captured the everyday—musicians playing their instruments, dancers swaying to forgotten rhythms, families gathered in moments of quiet joy. I could almost hear the laughter of children and the chatter of merchants as I gazed at a terracotta scene of a mother cradling her child, its details so vivid I felt I could reach out and touch them. These artworks spoke of a society that was both deeply spiritual and joyfully human, influenced by far-flung cultures—Greek, Persian, Southeast Asian—yet distinctly Bengali in its soul.

At the on-site museum, I lingered over a display of terracotta plaques depicting scenes from the Ramayana, their intricate carvings telling tales of heroism and devotion. A winged female deity, her form both ethereal and fierce, seemed to watch over me as I marvelled at the craftsmanship.

These pieces, many now housed in museums like the Ethnological Museum in Berlin and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, are a testament to the artistic genius of Chandraketugarh’s people. Yet, standing there, I couldn’t help but feel a pang of sorrow knowing that many of these treasures had been scattered across the globe, some lost to illegal trade and neglect.

Khana’s Prophecy: A Legend Etched in Earth

One of the most captivating stories tied to Chandraketugarh is that of Khana, a woman whose intellect and foresight have become the stuff of legend. Said to be the daughter-in-law of the renowned astrologer Varahamihira, Khana was a scholar and seer whose predictions, known as Khanar Vachan, are still recited in Bengali households. Local lore tells of her extraordinary abilities, which some say threatened the patriarchal order of her time. As I stood atop Khana Mihirer Dhibi, the five-meter-high mound named in her honour, I imagined her gazing at the stars, unravelling the mysteries of the cosmos.

Excavations at this mound, conducted between 1956 and 1968, unearthed the remains of a grand post-Gupta temple complex, its stones whispering of a time when devotion and knowledge flourished here. Khana’s story, though steeped in myth, feels like a bridge between the tangible ruins and the intangible spirit of Chandraketugarh. It’s a reminder that this city was not just a hub of trade and art but also a place where ideas and wisdom thrived.

Rediscovering a Lost City

Chandraketugarh might have remained buried in obscurity if not for the keen eye of Tarak Nath Ghosh, a local physician who, in the early 20th century, noticed artefacts during road construction. His discovery sparked curiosity, though the Archaeological Survey of India initially dismissed the site’s significance. It wasn’t until archaeologist Rakhal Das Banerji published his findings in 1920 that the world began to take notice. Decades of excavations followed, revealing city walls, gateways, temples, and a wealth of artefacts that painted a vivid picture of a once-thriving metropolis.

As I walked through the ruins, I could almost see the outlines of the ancient city—its streets bustling with traders, its temples alive with chants, its artisans shaping clay into stories that would outlive them. The discovery of Roman coins and other foreign artefacts hinted at Chandraketugarh’s far-reaching connections, a reminder that this was a city of the world, not just of Bengal.

The Fight to Preserve a Legacy

Yet, for all its historical significance, Chandraketugarh faces an uncertain future. Illegal excavations and artefact smuggling have robbed the site of many treasures, with countless pieces now displayed in museums far from their homeland. The West Bengal government’s establishment of a museum in 2017 was a crucial step toward preservation, offering a space to house and protect the remaining artefacts while educating visitors about the site’s importance. Standing in the museum, surrounded by relics of a lost world, I felt a renewed sense of urgency to protect this heritage for future generations.

A Call to Connect with the Past

Visiting Chandraketugarh was more than a trip—it was a pilgrimage, a chance to walk in the footsteps of a civilisation that shaped the cultural tapestry of Bengal. The ruins, though weathered by time, still convey a sense of resilience, creativity, and connection. The terracotta figurines, the temple mounds, the stories of Khana—they all weave together to form a narrative that is both deeply personal and universally human.

For anyone with a passion for history, Chandraketugarh is a must-visit destination. It’s a place where the past feels alive, where every fragment of clay and every weathered stone tells a story. Pair a visit here with a trip to Kolkata, where the vibrant culture of Bengal—its food, music, and traditions—continues to thrive.

As I left Chandraketugarh, the sun dipping low over the fields, I carried with me a sense of awe and responsibility. This is a place that deserves to be remembered, not just for what it was but for what it teaches us about who we are.

Chandraketugarh is more than a forgotten city—it’s a voice from the past, refusing to be silenced, calling us to listen, learn, and preserve its legacy for the future.

Frankly, before you mentioned the name of the place during our wa discussion, I haven’t heard of it ever though my maternal home was very close to Barasat and I used to visit the place quite regularly every year…

Hats off to your tenacity to research on the subject and publish such interesting article…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Aro. Next time, if you get time then do visit this place.

LikeLike

Have you been to Chadraketugarh? If not, then we can plan together.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Let’s plan it and go there. We will also visit Pandu Rajar Dhibi. It’s related to Pandu king of Mahabharata. The excavation indicates it to ca. 1500 BCE

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think we can plan it after the Durga/ Kali Puja … Some time in November. Can also include our culinary expedition of Kolkata that we have been postponing. 😁

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, let’s plan and go. We will only include like-minded langots.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wonderful. The pathetic state of affairs. Not only here but at many places in India.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re right, sir.

LikeLike

There is a novel by Bani Basu titled Khanamihirer Dhipi for which she was awarded the Sahitya Akademi award couple of years back.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for adding the reference of the lovely novel. It’s worth a read.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow, such a huge heritage and I wasn’t aware of. I am sure many Bengalis are not aware of this place or the heritage. Thanks for your research and sharing it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Nilanjana. You’re right. We are not caring for our past and heritage beyond Tagore.

LikeLike

Wonderful research work Indro. A very important piece of article on ancient Bengal. I think the artefacts excavated were polished and coloured, looking absolutely fresh.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Mano. Sadly, the ancient sites of Bengal are less excavated and much less published. It’s our heritage, which many of us are totally unaware of.

LikeLike

Such important art. I always learn so much from your blog!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Georgia for this inspirational remark.

LikeLike

A day-tour was arranged to Chandraketugarh from our school. The condition was pathetic back then too. In fact, we were terribly disappointed! However, I’ve learned that the government has arranged some securities now, but illegal activities, as you have mentioned, is still prevailing.

Thanks for the related piece of history. Informative, as always… 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Maniparna.

LikeLike

India is full of surprises. Never heard of this amazing place… and the legend of Khana is great! Thank you for sharing, Sir!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, India is full of treasures strewn around, but due to social and government apathy, many are getting extinct, sadly. Thanks, Shivangi.

LikeLiked by 1 person

True Sir🙏🏻

LikeLiked by 1 person

beautiful post with information of this historical place..

Thanks for sharing..

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, sir.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Kolkatar eto kachhe kintu naam e toh sunini. Ekdom keu jane na. Ei rastay gechhi o. Ki jata yaar! Khon abd Varahamihir were from Bengal! By god, jenei toh jete ichhe korchhe.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, this is because of our Bengalis and government apathy. Do visit this place in your next trip to Kolkata.

LikeLike

Thank you for shedding light on the lesser-known archaeological sites in Bangladesh. Your post has sparked my curiosity to delve deeper into its hidden gems.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, James. I feel privileged.

LikeLike

Pingback: Gangaridai: The Kingdom That Defied Conquerors – Indrosphere