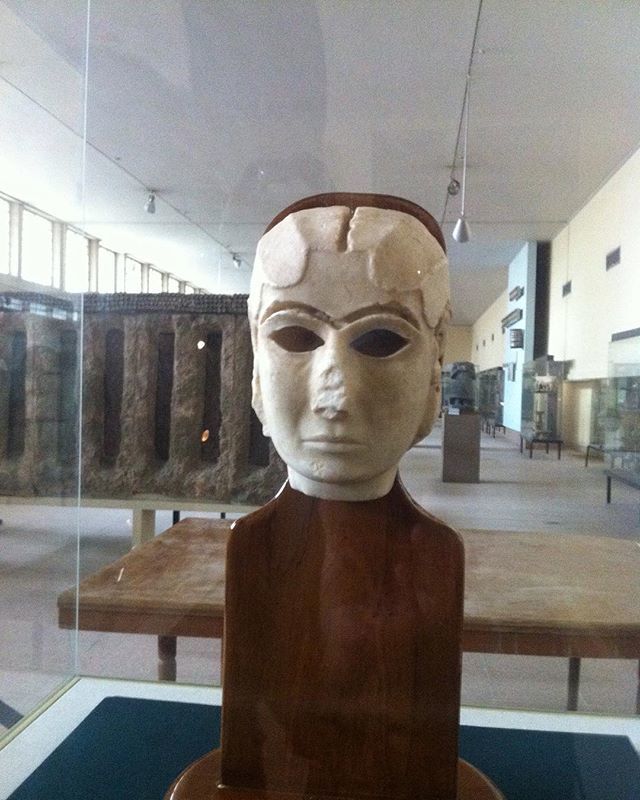

In the heart of ancient Mesopotamia, where the first cities rose from the fertile plains between the Tigris and Euphrates, a marble face emerged from the sands of time—serene, symmetrical, and hauntingly lifelike. Known as the Mask of Warka, or the Lady of Uruk, this 5,000-year-old artefact is one of the earliest known representations of the human face in sculpture. More than just a relic, it is a portal into the spiritual, artistic, and societal depths of one of humanity’s earliest civilisations.

The Mask of Warka was uncovered in Uruk, one of the most important cities of ancient Mesopotamia, located in what is now modern-day Iraq. Uruk is often regarded as the birthplace of urbanisation and monumental architecture, marking the transition from village life to complex city-states. The city is associated with several key innovations, including the development of writing (cuneiform), the construction of massive temples (ziggurats), and the rise of religious and political institutions.

It is the earliest known representation of the human face that was most likely an embodiment of the Goddess Inanna, the Sumerian goddess of love, war, beauty, sex and fertility. It is so realistic and detailed that it almost looks like a photograph.

In 1939, German archaeologists led by Dr. A. Nöldeke uncovered the Mask of Warka during excavations at Uruk. Measuring approximately 20 cm (8 inches) in height, the mask is carved from white marble, a rare and precious material in Mesopotamia. It is one of the earliest known naturalistic representations of the human face in sculptural form, a testament to the advanced artistry of early Mesopotamian civilisation. Its discovery marked a turning point in our understanding of early Mesopotamian art, revealing a sophistication that rivalled later classical traditions.

One of the most remarkable aspects of the Mask of Warka is its naturalistic depiction of the human face, a significant departure from the more stylised or abstract figures common in earlier art forms. The mask’s delicate features—arched eyebrows, almond-shaped eyes, and full lips—suggest that the Mesopotamian artists were already experimenting with techniques to capture the realism and the essence of the human form.

The craftsmanship displayed in the Mask of Warka is particularly noteworthy given the materials and tools available to the artisans at the time. The mask is carved from a single piece of marble, which would have required great skill and precision to shape. Though the eyes and eyebrows were originally inlaid with other materials (likely shell and lapis lazuli), these have been lost over time, leaving empty sockets that only hint at the original vividness of the sculpture.

The mask was likely part of a larger statue, possibly mounted on a wooden body, dressed in fine garments, and adorned with jewellery, reflecting the godly status of the figure it represented. The naturalistic style of the mask, combined with its sophisticated execution, illustrates a significant moment in the development of ancient art, where human likeness began to be rendered with increasing realism.

While the Mask of Warka is a masterpiece of early portraiture, its true significance lies in its religious symbolism. Scholars believe that the mask represents the goddess Inanna, one of the most important deities in the Mesopotamian pantheon. Inanna was revered as the goddess of love, beauty, fertility, and war, embodying both life-giving and destructive powers.

The choice to depict Inanna with such naturalism may reflect the Mesopotamians’ desire to humanise their gods, making them more relatable and accessible to worshippers. By giving Inanna a face that mirrored human beauty and expression, the artists of Uruk may have sought to bridge the gap between the divine and the mortal. This fusion of earthly and heavenly attributes is a common theme in ancient Mesopotamian religious art, where gods were often portrayed as idealised humans.

The mask’s placement in the Eanna temple complex further reinforces its divine connection. Eanna, the “House of Heaven,” was the most prominent temple in Uruk, and it served as a centre for religious rituals dedicated to Inanna. The Mask of Warka, therefore, was not just an artistic object but a powerful symbol of divine presence. It may have been used in processions, rituals, or ceremonies to invoke the goddess’s favour or protection.

In 2003, during the Iraq War, the Mask of Warka was looted from the National Museum of Iraq in Baghdad, along with thousands of other priceless artefacts. Its disappearance sparked international outrage and a massive recovery effort.

Thanks to the work of law enforcement, archaeologists, and military personnel, the mask was recovered undamaged later that year in a farmer’s yard near Baghdad. Its return was a symbolic victory for cultural preservation and a reminder of the fragility of heritage in times of conflict.

The Mask of Warka represents a pivotal moment in the history of art and religion. Its influence can be traced through subsequent Mesopotamian art, where naturalism continued to evolve alongside more stylised representations of divine figures. The mask’s realism set a precedent for future artistic endeavours, as artists throughout Mesopotamia and beyond continued to explore the boundaries of human likeness and expression.

Beyond its artistic and religious significance, the Mask of Warka also holds an enduring fascination for modern audiences. As one of the earliest known depictions of the human face, it offers a window into the world of ancient Mesopotamians, revealing how they saw themselves and their gods. For historians, archaeologists, and art lovers alike, the Mask of Warka remains a powerful symbol of humanity’s quest to understand and represent the divine.

The Mask of Warka is more than an archaeological treasure—it is a mirror to humanity’s earliest dreams. In its marble contours, we see the birth of art, the rise of cities, and the longing to understand the divine. It reminds us that even in the dawn of civilisation, people sought to capture the essence of life, beauty, and belief. Today, it continues to inspire awe and admiration, reminding us of the profound legacy of Mesopotamian art and its lasting impact on human culture.

As I stood before the Lady of Uruk, her gaze—carved in stone over five millennia ago—pierced through the veil of time. It was not merely the face of a goddess, but a reflection of humanity’s enduring quest to understand the divine. In her serene expression, we see the ancient yearning to embody beauty, power, and cosmic connection in tangible form.

The Mask of Warka does more than represent a forgotten civilisation—it speaks to us still, reminding us that the impulse to create, to revere, and to seek meaning is as old as civilisation itself. In her timeless gaze, we glimpse not just the soul of ancient Mesopotamia but the shared spirit of all who have ever looked to the heavens and wondered.

Stunning. While many of us know of it, it is still heartwarming to read about the rich history of a region beset by needless war and destruction in the recent past.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, sir.

LikeLike

Nice sculpture with amazing details and it is more than 5100 years old!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Nilanjana.

LikeLike

The art work truly depicts the artisan’s hadwork and insight.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very informative as usual…

You can easily write a historical thriller based on your vast knowledge of the “old world” …

Eagerly look forward to a serialised piece… 😊

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hahaha! Thanks, Aro.

LikeLike

Wonderful information. The mask looks quite nice. Thanks for sharing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Sanchita.

LikeLike

Amazing..

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, sir.

LikeLike

Wonderful historical information once again. Hoping to get more such articles on old Babylonian / Mesopotemian civilisation.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Mano.

LikeLike

Wonderful historical information once agai. Hoping to get more such articles on Babylonian / Mesopotemian civilisation.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Mano.

LikeLike