When we think of India’s struggle for independence, our minds often drift to the familiar imagery—salt marches under the scorching sun, the rhythmic hum of spinning wheels, and the stoic figure of Mahatma Gandhi leading the nation with the force of nonviolence.

But behind this public face of peaceful protest, another current surged—fierce, secretive, and uncompromising. It was a movement that refused to bend before the Empire’s will, that chose the bomb and the bullet over the petition and the plea. At the beating heart of this defiant underground stood the Anushilan Samiti—a revolutionary fraternity that dreamed of freedom through fire.

The Birth of a Secret Brotherhood

The early 20th century in Bengal was a furnace of discontent. The moderate petitions of the Indian National Congress had failed to break the chains of colonial rule, and a new generation was growing impatient. Into this charged atmosphere was born the Anushilan Samiti—literally, the Practice Association.

The inception of the Anushilan Samiti holds a captivating narrative. Initially conceived as a society promoting youth engagement and physical fitness through activities like lathi play, it soon evolved into a vehicle for social welfare endeavours, particularly aiding Calcutta’s marginalised communities. Over time, its ranks swelled in membership and scope, earning recognition for its fervent nationalism.

On the surface, it seemed harmless enough: a youth fitness club devoted to physical culture, lathi drills, and sword practice. But the founders—Satish Chandra Basu, Pramathanath Mitra, Sarala Devi, and the dynamic Ghose brothers, Aurobindo and Barindra Kumar—had far greater ambitions. They were not simply building bodies; they were forging warriors.

From a modest start in Kolkata, the Samiti spread like wildfire, evolving into a clandestine network of cells bound together by the dream of complete independence.

Training for Liberation

At the core of the Samiti’s philosophy lay Anushilan-tatva, inspired by Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay’s “Theory of Discipline.” Theirs was not mere physical training—it was a holistic preparation for rebellion.

Members studied history, political science, and economics alongside martial arts, bomb-making, and guerrilla tactics. They were groomed to think like strategists and act like soldiers.

The Anushilan Samiti was not a monolithic entity but rather a network of interconnected cells operating across different regions of British India, particularly in Bengal, Punjab, and Maharashtra. Despite being decentralized, the Samiti maintained a cohesive ideology centred around the principles of nationalism, socialism, and self-sacrifice. Its members, often drawn from educated urban youth and disaffected intellectuals, were willing to risk their lives for the cause of liberating their motherland.

“We teach the youth to awaken, prepare and strike—freedom will not be begged from the oppressor.”

One of the defining features of the Anushilan Samiti was its emphasis on physical fitness and martial training. Members engaged in rigorous exercises, martial arts, and weapon drills, preparing themselves for the eventual armed struggle against the British. This focus on physical strength and discipline not only served practical purposes but also instilled a sense of camaraderie and unity among the revolutionaries.

The Pen & the Pistol

“A new era demands action; words without sacrifice are a slow death for the nation.”

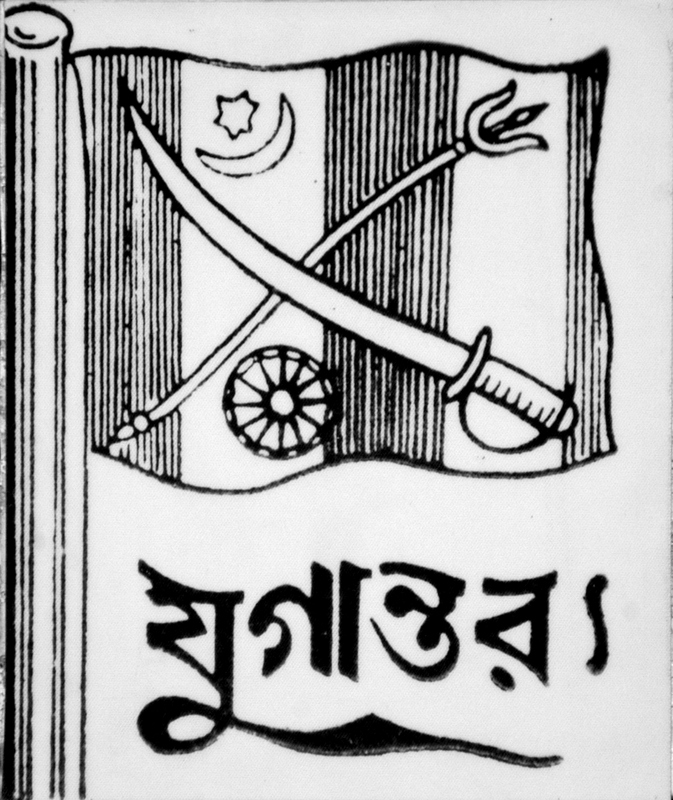

The revolutionaries knew that the fight for independence wasn’t only fought with weapons—it was also waged with words. Their publication, Jugantar, became a rallying cry for armed struggle. Through essays, pamphlets, and fiery editorials, they called on Indians to rise, resist, and reclaim their motherland.

This propaganda didn’t just preach revolt—it taught it. It explained the strategy behind their actions, the urgency of the hour, and the moral justification for taking up arms. The Samiti’s leaders were as much thinkers as they were fighters.

“Jugantar proclaims that political violence is justified when all peaceful remedies have failed.

Strikes of Defiance

The Anushilan Samiti’s operations were neither random nor reckless—they were deliberate acts aimed at shaking the foundations of British power.

From targeted assassinations of oppressive officials to coordinated bombings and raids, each mission was designed to inspire a broader uprising. Names like Rash Behari Bose and Bagha Jatin became synonymous with daring and sacrifice.

“The times call for the sacrifice of blood and fortune for the motherland.”

Their actions rattled the British administration and inspired countless young Indians to question whether nonviolence was the only path to freedom.

Ripples Across the Freedom Struggle

The ideas and spirit of Anushilan Samiti continued to influence later revolutionary movements in India, such as the Hindustan Republican Association (later Hindustan Socialist Republican Association) led by Bhagat Singh. The Hindustan Republican Association emerged as a fresh entity affiliated with the Anushilan Samiti, established in Benares in 1923. With its radical ideology, it played a pivotal role in fostering the spirit of nationalism, particularly in the northern regions of India.

Despite facing repression and surveillance from the British authorities, the Anushilan Samiti continued to operate clandestinely, evolving its tactics to adapt to changing circumstances. It forged alliances with other revolutionary groups and played a significant role in the Ghadar Movement, which aimed to incite a rebellion against British rule among Indian soldiers stationed abroad.

Subhas Chandra Bose & the Last Push

By the 1940s, as World War II distracted the British, the Samiti sensed a new opening. Subhas Chandra Bose, drawn to its radical zeal, aligned himself with its vision.

Plans were laid for mass uprisings, alliances with trade unions, and coordinated sabotage of colonial infrastructure. Student movements swelled, communist literature circulated, and the dream of a nationwide rebellion began to flicker brighter than ever.

But the British struck quickly and decisively—arresting Bose and key leaders, cutting the head off the planned insurrection. The grand plan collapsed, but the spirit behind it refused to die.

Legacy of Fire

The legacy of the Anushilan Samiti in India’s independence movement is profound. While its methods may have been controversial to some, its commitment to the cause of liberation and its willingness to confront colonial oppression head-on inspired generations of revolutionaries. The Samiti’s spirit of defiance and sacrifice laid the groundwork for the eventual overthrow of British rule in India.

Its methods might be controversial. Its path was perilous. But its impact was undeniable. It challenged the comfortable narrative that India’s independence was won solely through passive resistance, reminding the world that there were those willing to risk—and lose—everything in open defiance.

As we celebrate the fruits of sovereignty today, it is worth pausing to remember these men and women of the shadows. Their story is not one of quiet petitions or negotiated settlements, but of courage forged in secrecy, of sacrifice made without guarantee of victory.

The Anushilan Samiti’s legacy is a reminder that freedom is rarely given—it is taken, wrested from the grip of empire by those with the audacity to fight for it.

Nice post on Anushilan Samiti, Indrajit. It is necessary to stress that we have got the independence not just because of Gandhiji and his Satyagraha.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Nilanjana.

LikeLike

Unfortunately, we were not taught about the real revolutionaries in our history lesson.

अब जा के समझ आया कि चरखा तो बस दिखावा था, आजादी तो आखिर खून बहा के ही मिला हमें ।

LikeLiked by 2 people

During World War II, India’s industrial growth contrasted sharply with England’s mounting war losses. By the war’s end, the British Empire was severely weakened, both politically and economically, lacking the resources to maintain control over its colonies. Several factors converged to pave the way for India’s independence. The war had left Britain depleted, making it increasingly unlikely that they could continue to dominate India. In 1946, the Royal Indian Navy went on strike, protesting poor working conditions and low pay, further undermining British authority. Additionally, escalating violence between Hindus and Muslims strained British control even more.

Earlier, the British had attempted to weaken the burgeoning nationalist movement in Bengal by partitioning the province in 1905, under the orders of Lord Curzon. The partition was designed to divide Bengalis along religious and territorial lines, triggering a wave of radical nationalism. Nationalists across India rallied behind Bengal, outraged by what they perceived as a British “divide and rule” strategy. Protests erupted in regions like Bombay, Pune, Uttar Pradesh, and Punjab. The unrest linked to the Swadeshi movement eventually led Lord Hardinge to reverse the partition. In 1911, King George V announced at the Delhi Durbar that eastern Bengal would be reintegrated into the Bengal Presidency, a move that also involved shifting the capital to New Delhi to strengthen British administrative control.

The stories of the Indian National Army (INA), led by Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose, and its battles during the Siege of Imphal and in Burma, captured the public’s imagination and fueled discontent. The Royal Indian Navy mutiny in 1946, driven by these stories and widespread dissatisfaction, marked a significant turning point. Although the mutiny ended with the sailors surrendering to British authorities, it signaled the final blow to British rule in India. The Indian National Congress and the Muslim League, concerned about the potential political and military consequences of such unrest on the eve of independence, urged the sailors to surrender, realizing that a peaceful transition of power was essential for the nation’s future.

The cumulative effect of these events, mass demonstrations like Quit India movement initiated by the Indian national Congress, along with rising tensions between Hindus and Muslims, set the stage for India’s independence, as the British could no longer suppress the growing demand for freedom.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Nice post

LikeLike

Thank you, Satyam.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Khudiram Bose: The Boy Who Smiled at the Noose – Indrosphere