As the holiday approached in Iraq, a sense of anticipation filled the air. With the extended weekend marking the Kurdish New Year, Nowruz, we—my friends and I—seized the opportunity to dive deep into the heart of Mesopotamian history. Our destination? None other than the National Museum of Iraq, also known as the Iraqi Museum. Nestled in the heart of Baghdad, the museum is an awe-inspiring treasure trove that holds the ancient soul of a land that has cradled civilization itself.

A Grand Welcome at the Iraqi Museum

As we approached the imposing entrance of the museum, we were greeted by the majestic statue of Nabu, the ancient Assyrian god of wisdom. Standing tall and proud, this sculpture felt like a fitting guardian to the vast collection that lay ahead—one that spoke to the ingenuity and resilience of a civilization that birthed much of the world’s early achievements.

A Walk Through Time

As we ventured further into the museum, it was impossible not to feel the weight of history. The diversity of artifacts on display was staggering. Each piece, from intricately painted pottery to life-sized sculptures, carried with it the whispers of the people who once lived here. The museum spans the ancient Sumerian, Akkadian, Assyrian, Babylonian, and Islamic cultures, providing a rich mosaic of human achievement.

The Iraq Museum was founded in 1923 when Gertrude Bell, the British woman who helped establish the nation of Iraq, stopped the archaeologists from taking out of the country all of his extraordinary third-millennium BCE finds from the ancient Sumerian city of Ur (esp. the jewellery of the royal cemetery) for division between the British Museum in London and the University of Pennsylvania’s Museum in Philadelphia. She believed that the Iraqi people should have a share of this archaeological discovery made in their homeland and, thereby, started a museum in central Baghdad, pressing into service two rooms in an Ottoman barracks as its very first galleries. Later on, the museum was shifted to this new premises and formally opened in 1966.

The Dark Chapter: Looting and Loss

Despite the museum’s brilliance, it is impossible to ignore the shadows cast by the tragic events of 2003. In the chaos following the U.S. invasion, the museum was plundered. Thousands of invaluable artifacts were stolen, leaving Iraq’s cultural heritage in tatters. The scale of the theft was staggering—estimates suggest that over 15,000 objects were taken, including priceless pieces from ancient Sumerian, Akkadian, and Assyrian civilizations.

In the chaotic, violent April of 2003, as US tanks rolled into Baghdad, the Iraq Museum was broken into and pillaged. Looters rampaged through the halls, storerooms, and cellars, stealing more than 15,000 precious objects. Iraqi officials estimate that as many as 137,000 pieces, in addition to 15,000 registered artefacts, were looted from the museum and archaeological sites across the country.

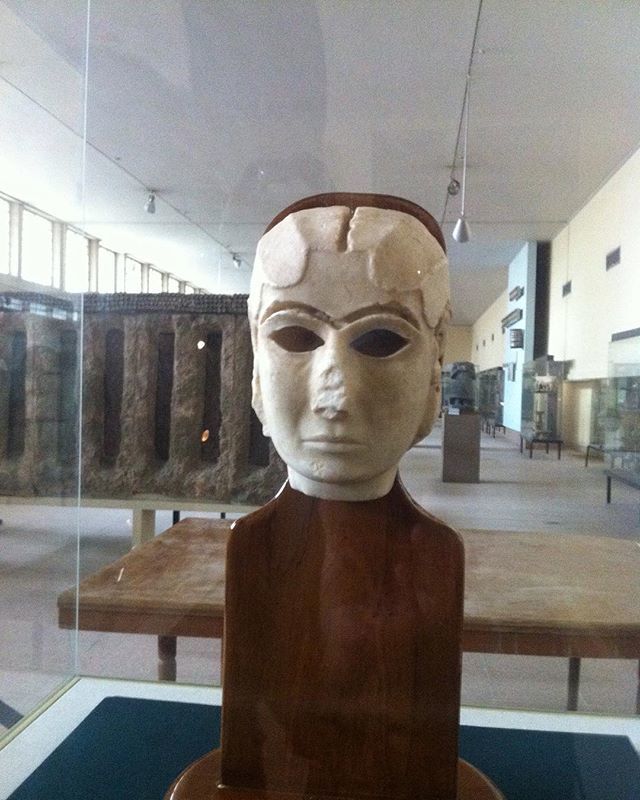

Despite the chaotic situation and rampant plundering of Iraq’s cultural heritage, the restored museum still harbours unique items that have been recovered, including the Warka vase, which reflects Sumerian philosophy of life and death; the Warka Lady’s stone head; and the Sumerian guitar, the most ancient musical instrument in the world. The collections of the National Museum of Iraq include art and artefacts from ancient Sumerian, Babylonian, Akkadian, Assyrian, and Chaldean civilizations.

The loss was not only a blow to Iraq but to the world, as many of these artifacts were irreplaceable links to our collective human past. Yet, during this darkness, there is a glimmer of hope. The museum has worked tirelessly to recover many of these stolen treasures, and items like the Warka Vase and the Lady of Warka have found their way back home.

The Iraq Museum is still one of the best archaeological museums in the world, containing material evidence for the development of civilised human society from the very beginning of its history.

The museum’s collection is a testament to the remarkable diversity and creativity of Mesopotamian cultures. From intricately crafted pottery to majestic sculptures, each artifact tells a unique story of the people who once inhabited this region. I was particularly fascinated by the Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III, a towering stone monument that depicts the Assyrian king’s military conquests and triumphs. It offered a fascinating glimpse into the ancient world of warfare and diplomacy.

Another highlight was the skeletal remains of a Neanderthal man, discovered in Shanidar Cave in northern Iraq. This remarkable find provided valuable insights into the evolution of early humans and their adaptation to the harsh environment of Mesopotamia.

The Heart of the Museum’s Story: The Lady of Warka

Among the many gems of the museum, the Lady of Warka stands out as a symbol of Iraq’s rich cultural legacy. Known also as the Mask of Warka, this marble face, dating back to around 3100 BCE, is believed to depict Inanna, the ancient Sumerian goddess of love, fertility, and war. What makes this mask particularly unique is that it is the earliest known accurate depiction of a human face.

During our visit, a conference was underway on the significance of this piece, adding a layer of depth to its already profound presence. Interestingly, the Lady of Warka had a tumultuous history. After the devastating looting of the museum in 2003, it was believed to be lost forever. However, miraculously, the mask was found undamaged, buried in a farmer’s backyard, a symbol of Iraq’s enduring spirit in the face of calamity.

Hatra: A Glimpse Into the Hellenistic and Parthian Periods

Hatra (Al-Hadr in Arabic) is located in the Al-Jazira region between the rivers Tigris and Euphrates. Their written language was Aramaic. Hatra is believed to have been built by the Assyrians or possibly in the 3rd or 2nd century BCE under the influence of the Seleucid Empire.

As we continued our journey through the museum, we were transported to the ancient city of Hatra, located between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. Hatra flourished during the 1st and 2nd centuries CE, a period when Parthian influences blended with Hellenistic traditions. The remains of the city, including intricately carved reliefs and statues, offered a glimpse into the cultural fusion that once defined Mesopotamian civilization.

Hatra flourished under the Parthians, during the 1st and 2nd centuries CE, as a religious and trading centre. The remains of the city, especially the temples, were Hellenistic and Roman architecture blended with Eastern decorative features, attest to the greatness of its civilization.

The Assyrian Hall: The Power of Kings and Gods

The final leg of our journey took us to the Assyrian Hall, a space that exuded the power and grandeur of one of Mesopotamia’s most formidable civilizations. Here, we stood in awe before colossal statues of Assyrian gods and kings, including another monumental representation of Nabu. His towering presence seemed to speak directly to the heart of the ancient world, where knowledge, power, and wisdom intertwined.

Nabu is the ancient Mesopotamian patron god of literacy, the rational arts, scribes, and wisdom. Nabu was worshipped by the Babylonians and the Assyrians. Nabu replaced Nisaba in the Sumerian pantheon and gained prominence among the Babylonians in the 1st millennium BCE when he was identified as the son of the god Marduk. He was also the inventor of writing and a divine scribe. Due to his role as an oracle, Nabu was associated with the Mesopotamian moon-god Sin.

A big pottery jar with Barbotine decorations with designs and motifs of lion heads, animals, human face, plant and geometric motifs found in Mosul belonging to the fourteenth century.

Reflections on Resilience and Hope

As I left the museum, I felt a profound sense of awe and respect. The National Museum of Iraq is not just a collection of ancient artifacts; it is a testament to the resilience of the Iraqi people and their unbreakable connection to their past. Despite the challenges and upheaval that the country has faced, the museum continues to stand as a beacon of hope, a symbol of Iraq’s enduring cultural spirit.

A Call to Action

I encourage everyone to visit the National Museum of Iraq—whether in person or virtually—and experience the wonders of Mesopotamian civilization for themselves. It is not just a museum; it is a living history, a narrative of humanity’s beginnings, struggles, triumphs, and rebirths. By supporting the museum’s efforts to preserve and share this invaluable heritage, we ensure that Iraq’s story will continue to inspire generations to come.

Thank you for joining me on this virtual journey through the National Museum of Iraq. I hope it ignites your curiosity and appreciation for the incredible history of this ancient land. Until next time, may your travels lead you to places that challenge and inspire you.

Happy explorations!

Indeed it does look like one of the best museums for ancient history.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes, Arvind and it would have been much better had it not been looted.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Absolutely!

LikeLiked by 2 people

It is interesting to know that a British lady helped to establish the Museum of Iraq and stopped the archaeologists from taking out of the country all the treasured artefacts. I am of the opinion that a country’s artefacts should remain within a country.

Yet, though I may never get a chance to see the museum of Iraq, I can relate to some of these artefacts as many of these were present in the Museum of Pennsylvania and the British Museum, and I had a chance to visit both these museums.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes, I am also of the same opinion that relics of the country must remain with them. But most of the important relics are in the British museum, Louvre or in the Universities of the US. They took the advantage of the western imperialism in the 19th and 20th centuries.

LikeLiked by 2 people

True that. Louvre, Paris is on my wishlist,

LikeLiked by 2 people

Hello, Indrajit. Your post reminds me the memory of reading the history book of school days.Babylon, The Mesopotamia civilization, etc hit my brain to remember the story of the civilization. I don’t know, whether I can visit Iraq or not. But, from now I’m including Iraq travel on my bucket list. Very nice post.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Iraq is full of history. Unfortunately, many historical sites have been damaged, lost. The situations are improving in Iraq. I wish you can make it to Iraq one day.

LikeLike

Pingback: 10 coisas importantes que foram destruídas pela guerra | Brasilempauta.com

Pingback: 10 Important Things That Were Destroyed by War - Random Review

Pingback: 10 Important Things That Were Destroyed by War - Billionaire Club Co LLC

Pingback: 10 coisas importantes que foram destruídas pela guerra - Brasil em Pauta Notícias

Pingback: Hatra – sculptures – COLORS & STONES