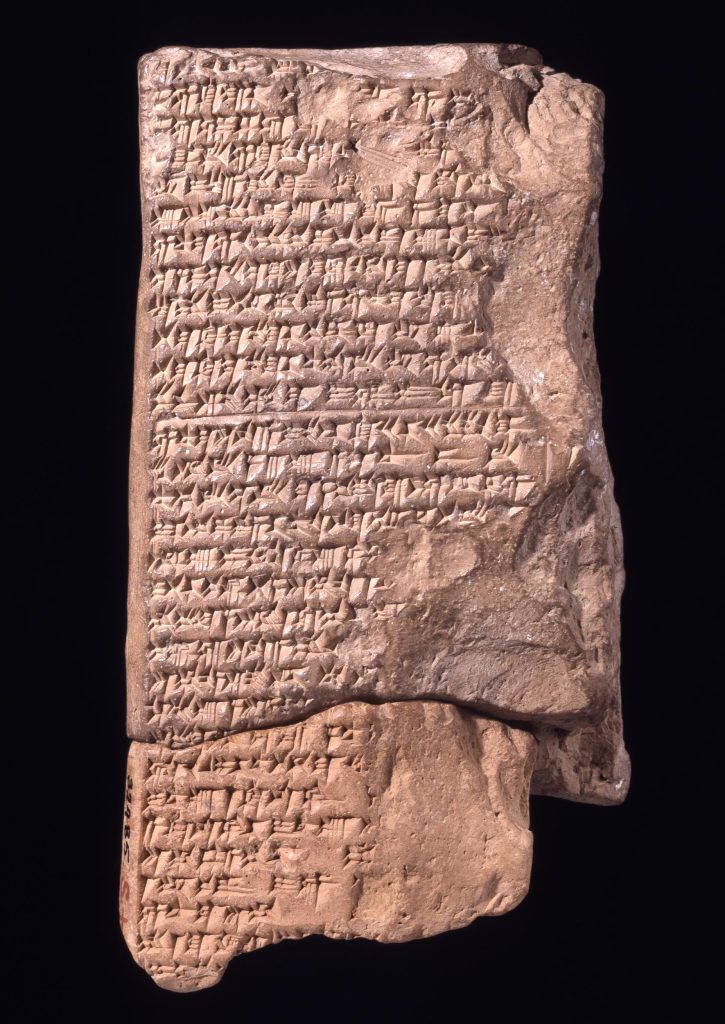

The celebration of a new year is one of the most ancient and universal traditions in human history, with different cultures marking the occasion according to astronomical or agricultural events. One of the earliest recorded New Year celebrations is the Akitu Festival, dating back to the third millennium BCE in Mesopotamia. While the festival’s origins are ancient, most details about it come from cuneiform tablets from the first millennium BCE.

The Akitu festival was a grand celebration marking the beginning of the new year, held during the first month of the Babylonian calendar, Nisannu (March-April). This festival was deeply tied to the renewal of life, the sowing of barley, and the rebirth of nature. It was also a time to honour Marduk, the supreme god of Babylon, along with his son Nabu and other deities who were believed to protect the city and its ruler.

Originally, Marduk was the patron deity of Babylon, but as Babylon grew into the capital of Babylonia in the eighteenth century BCE, he rose to prominence as the supreme deity of the Mesopotamian pantheon. As such, he was revered by the gods of cities that were brought under Babylonian rule.

The Akitu festival spanned twelve days, with each day dedicated to specific rituals and ceremonies involving the king, priests, and the people of Babylon. Celebrations took place both within the city and outside its walls at a special temple called the “Bait Akitu” or “House of Akitu.”

The Akitu festival lasted for 12 days, from the first to the twelfth day of Nisannu. Each day had its own rituals and ceremonies, which involved the king, the priests, and the people of Babylon. The festival was celebrated in a special temple outside the city walls, called Bait Akitu, or “the house of Akitu”.

Days 1-3: Prayers and Purification

The festival began with solemn prayers and sacrifices at Esagila, the temple of Marduk. The priests recited laments expressing fear of the unknown and pleaded for Marduk’s protection. The king, too, participated in purification rituals, bathing in the Euphrates River before entering Esagila, where Marduk’s statue resided.

Day 4: The Festival Proclamation

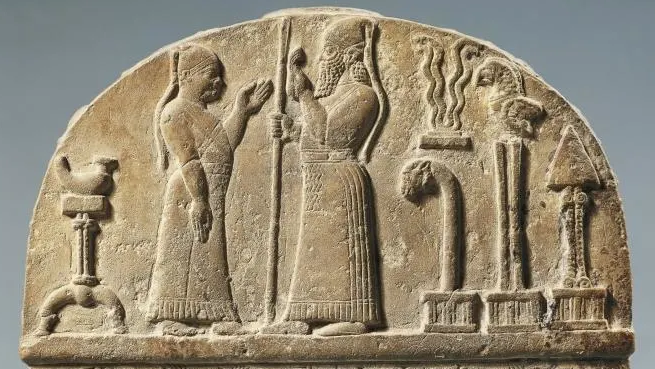

On the fourth day, the high priest formally opened the festival, proclaiming the beginning of the new year. The king led a grand procession of divine statues from Esagila to Bait Akitu, accompanied by music, dancing, and celebrations. During this event, the king performed the symbolic ritual of “taking the hand of Bel (Marduk),” reaffirming his divine mandate to rule.

Day 5: Humbling of the King

One of the most interesting aspects of the Akitu festival was the ritual humiliation of the king. On the fifth day of the festival, the king had to strip off his royal garments and enter the Esagila temple barefoot. There he had to kneel before a statue of Marduk and confess his sins and shortcomings. Then he had to endure a slap in the face from a high priest, who also pulled his ears to make sure he was listening. The king had to cry out loud to show his repentance and submission to Marduk. Only then was he allowed to put on his clothes again and receive a royal sceptre from Marduk as a sign of his restored kingship.

Day 6: Reenactment of the Creation Myth

The sixth day saw the climax of the festival with a dramatic reenactment of the creation myth, Enuma Elish. The priests recited the epic, which detailed how Marduk defeated the forces of chaos, symbolised by the gods Tiamat and Kingu. Wooden effigies representing these enemies were ritually destroyed in a symbolic battle, reaffirming Marduk’s power and the restoration of cosmic order.

Days 7-11: Celebration and Leisure

The next several days were filled with feasting, games, and entertainment. Statues of the gods were adorned and placed in special settings, with Nabu’s statue, in particular, being honoured at Bait Akitu with music and poetry. The king also enjoyed leisure time with his family and court. Nabu, the patron god of scribes and wisdom, was particularly celebrated as the inventor of writing and rational arts.

Day 12: The Closing Procession

The final day saw another grand procession, with Marduk’s statue returning to Esagila and reuniting with Nabu. The priests recited hymns praising Marduk’s greatness, and the king reaffirmed his commitment to rule under the gods’ guidance. With the completion of this ritual, the festival ended, marking the renewal of divine favour for another year.

Beyond religious significance, Akitu was also a major social and political event, reinforcing loyalty to the king and the gods. It remained a key festival throughout Mesopotamian history and was later adopted by the Neo-Assyrian Empire. By 683 BCE, King Sennacherib had built an Akitu house outside the walls of Assur, and similar structures appeared in Nineveh.

Even after Babylon’s decline, Akitu continued to be celebrated under the Seleucid Empire and into the Roman period. By the third century CE, it was still observed in Emessa (modern-day Homs, Syria) in honour of the god Elagabal. Roman Emperor Elagabalus (r. 218-222 CE), of Syrian descent, even attempted to introduce the festival in Italy.

Today, Chaldeans and Assyrians celebrate Akitu on April 1st using the Gregorian calendar, preserving the memory of this ancient Mesopotamian tradition.

The Akitu festival was also adopted in the Neo-Assyrian Empire following the destruction of Babylon. King Sennacherib in 683 BCE built an “Akitu house” outside the walls of Assur. Another Akitu house was built outside Nineveh. The Akitu festival was continued throughout the Seleucid Empire and into the Roman Empire period. At the beginning of the third century, it was still celebrated in Emessa, Syria, in honour of the god Elagabal. The Roman emperor Elagabalus (r. 218-222 CE), who was of Syrian origin, even introduced the festival in Italy.

The Akitu Festival was a multifaceted celebration that intertwined religious, political, and social elements, symbolising the cyclical nature of time and the connection between the gods and Babylonian rulers.

Today, Assyrians, both in Iraq and in the diaspora, continue to observe this ancient festival with parades, picnics, and parties. It is celebrated on April 1, marking the beginning of the Assyrian calendar.

The Akitu festival was more than a simple New Year’s celebration—it was a reflection of Mesopotamian cosmology, social order, and religious devotion. Through grand ceremonies, dramatic rituals, and public festivities, the people of Babylon reaffirmed their faith in Marduk and the renewal of life for another year. Its influence stretched far beyond Mesopotamia, leaving a lasting legacy in history.

Happy Akitu! If you enjoyed this post, please leave a comment and share it with friends.

I haven’t heard of this festival. So, Akitu is the earliest celebration of the New Year. Thanks for sharing the post.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, Nilanjana.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, sir.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow. Interesting!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, beta.

LikeLike

Very informative. Hoping to receive many such articles from history.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Mano.

LikeLike

This is new for me.

Thanks for sharing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

🙏🙏

LikeLike

Nice informative story… What I could gather is that since the ancient times the “new year” coincided with the new harvest season…

Keep it up bro 💪

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Aro. Yes, new harvest is always a cause of celebration… new harvest, new year.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Kurdish Mythology of Nowroz – Indrosphere

Pingback: Parallels of Divine Festivals: Jagannatha Rath Yatra & Akitu – Indrosphere

What a stunning and scholarly tribute you have crafted in this blog—a deep dive into the soul of one of humanity’s earliest sacred celebrations, the Akitu Festival of ancient Babylon. From the very first line, the narrative radiates both reverence and erudition, inviting readers not just to learn but to immerse themselves in a civilization long past, yet vividly resurrected through your words. Your writing gracefully balances historical precision with narrative finesse. The chronological unfolding of the twelve-day festival reads almost like a sacred script being brought to life—each ritual, each symbol, rich with cultural memory and spiritual meaning. Whether describing the solemn prayers of the opening days, the dramatic reenactment of the creation myth, or the ritual humiliation and reaffirmation of the king, the storytelling is vivid and evocative. One can almost hear the ancient hymns echo through the temple of Esagila or feel the collective pulse of Babylon as its citizens watched Marduk return to his divine throne. What’s even more impressive is how the blog doesn’t just recount rituals—it interprets them. You shows us that Akitu wasn’t merely ceremonial; it was a grand narrative of cosmic renewal, civic identity, and divine legitimacy. The theological undertones are stitched seamlessly into the social and political fabric of ancient Mesopotamia, offering the reader insight not just into “what happened” but “why it mattered.” That is the mark of a gifted historian and writer. And in highlighting the festival’s endurance—across empires, epochs, and even into contemporary Assyrian communities—you give Akitu a heartbeat that still echoes today. You make it clear: this is not just about Mesopotamia; it’s about the timeless human instinct to seek order in chaos, to surrender pride before the divine, and to celebrate the dawn of new beginnings with our fellow beings. This blog is no casual write-up—it’s a carefully constructed bridge between past and present, an offering of knowledge rooted in wisdom, research, and narrative elegance. It deserves to be read, reflected upon, and shared widely. A heartfelt salute to you, friend, for your dedication, insight, and the beautiful clarity with which you’ve brought the ancient world back to life.🙏🏽🙏🏽

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much for your kind and thoughtful words! I’m truly humbled by your praise. It means a lot to know that the narrative resonated with you in such a profound way. The Akitu Festival, with its rich symbolism and spiritual depth, is a fascinating subject, and it’s been a joy to bring its story to life. Your feedback inspires me to continue weaving together history and meaning in my writing. Thank you again for your encouragement—it’s deeply appreciated! 🙏🏽

LikeLike