As I wandered through the hushed corridors of the Iraq Museum in Baghdad, I found myself enveloped by the echoes of ancient civilisations. Each artefact whispered stories of empires long gone, but among the treasures that stirred my imagination, none stood as tall—both literally and symbolically—as the majestic Lamassu.

The Lamassu is a mythical creature born from the rich tapestry of Mesopotamian belief—a celestial hybrid with the body of a bull, the wings of an eagle, and the head of a human. Towering over visitors with its imposing form, it once stood guard at the entrances of Assyrian palaces and temples, a divine protector warding off chaos and evil.

In Assyrian lore, the Lamassu was more than mere ornamentation. It was a guardian spirit, a supernatural being entrusted with safeguarding both the divine and the mortal realms. Depending on the translation, it was referred to as a demon, genie, or protective deity. Regardless of the name, its role was clear: to protect, to inspire, and to awe.

During the reigns of Ashurnasirpal II (883–859 BCE) and Sargon II (721–705 BCE), the Lamassu became a prominent fixture in the architectural landscape of Assyrian capitals. These colossal sculptures, carved with astonishing precision, symbolised imperial strength and divine authority.

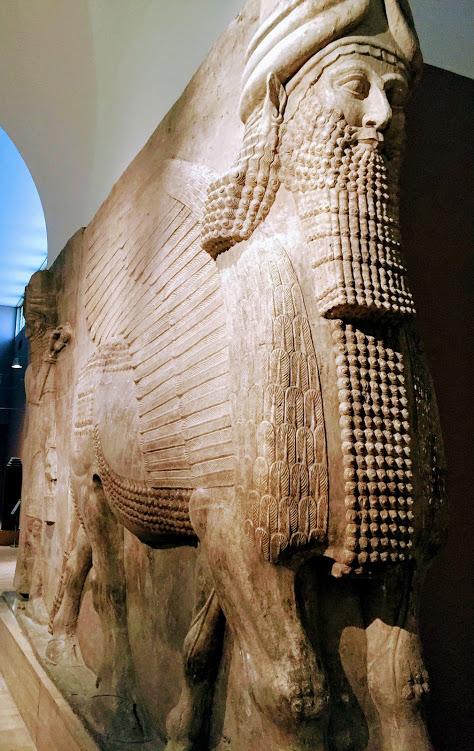

One particular Lamassu in the Iraq Museum, originally from Sargon II’s palace in Khorsabad, left me breathless. Standing over four meters tall and weighing more than 30 tons, this monolithic guardian was carved from a single block of limestone in the 8th century BCE. Its intricately detailed beard, feathered wings, and muscular frame spoke volumes about the artisans of ancient Mesopotamia—masters of form, symbolism, and storytelling.

Lamassu is clearly an intriguing creature, but where does it come from? The Lamassu is a celestial being from ancient Mesopotamian religion bearing the head of a man, the wings of an eagle, and the hulking body of a bull, sometimes with the horns and the ears of a bull.

The Lamassu’s roots stretch deep into Mesopotamian history. The earliest depictions date back to around 3000 BCE, with variations known as Lumasi, Alad, and Shedu. In Sumerian tradition, a protective female spirit named Lama served the gods, a precursor to the later Assyrian Lamassu. Over time, the figure evolved, becoming male, bearded, and even more formidable in stature.

The Assyrians envisioned the Lamassu as a composite being: part bull or lion for strength, part eagle for swiftness, and part human for intelligence. Interestingly, these sculptures were designed with five legs—two visible from the front and four from the side—creating the illusion of motion and stability depending on the viewer’s perspective.

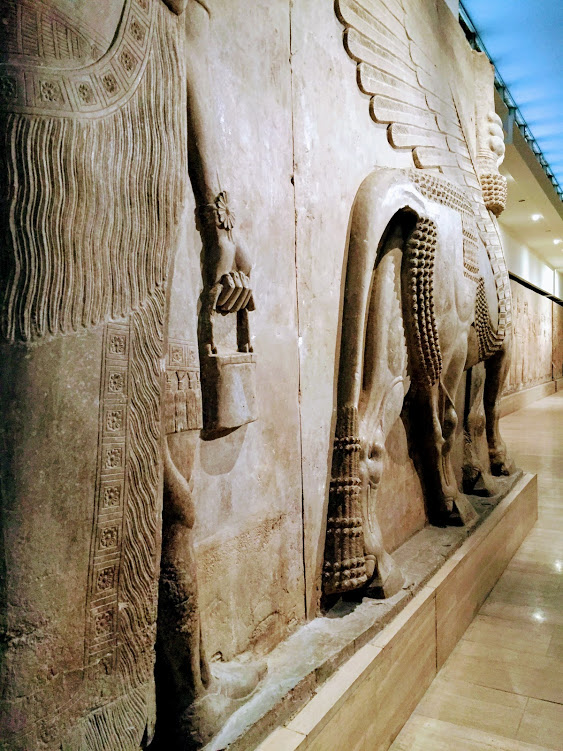

Alongside the Lamassu, Assyrian palaces featured winged genies—bearded male figures with bird-like wings, often holding pine cones and baskets. These genies, like the Lamassu, were symbols of divine protection and royal power. They adorned the throne rooms of Kalhu (modern-day Nimrud) and Dur-Sharrukin (Khorsabad), reinforcing the sacred nature of the king’s presence.

Every major Assyrian city sought the protection of the Lamassu at its gates. These figures weren’t just artistic marvels—they were spiritual guardians, believed to repel chaos and usher in peace. Their presence inspired armies and citizens alike, serving as a visual reminder of divine favour and imperial might.

The Lamassu is a striking example of Neo-Assyrian art, which flourished between 934 and 609 BCE. Relief sculpture was the dominant medium, with figures emerging from stone in dynamic poses that conveyed both motion and majesty. The Lamassu’s dual perspective—frontal and lateral—created a sense of living presence, as if the creature were actively watching over its domain.

Relief sculpture is by far the most striking manifestation of Achaemenian art. Adopted as the basis of the new style was the straightforward technique of the Assyrians, with its engraved detail and lack of modelling.

The representation of the human-headed winged bull is the cross of two perspectives, changing from high relief in the flat area (side view) to the full-relief view of the forward portion of the sculpture. The materialisation of the figure emerging from the raw stone block stresses the link between creature and palace, as well as dynamic power and motion to the visitors, and thus is intended to guard and protect against evil powers. The precarious balance between the motionless posture of the forward-looking portion and the dynamic movement of the side view gives rise to a sedate unsteadiness, bringing the creature to life.

The sculptures were meant to be seen in one of two ways – from the front, looking directly at the face, or from the side as the viewer entered the king’s throne room. Therefore, the figures are sculpted with five legs – two legs that can be seen from the front view and four legs that can be seen from the side. This would indicate that the figure was a four-legged beast, but the extra leg was added so that the side view made visual sense. The figures were carved in relief, that is, they were not free-standing sculptures but rather only part of the figure was carved, and they needed a wall to support them.

Every important city wanted to have a Lamassu protect the gateway to its citadel. At the same time, another winged creature was made to keep watch at the throne room entrance. Additionally, they were the guardians who inspired armies to protect their cities. The Mesopotamians believed that Lamassu frightened away the forces of chaos and brought peace to their homes. The most famous colossal statues of Lamassu have been excavated at the sites of the Assyrian capitals established by King Assurnasirpal II (r. 883 – 859 BCE) and King Sargon II (r. 721 – 705 BCE).

Even after the fall of the Assyrian Empire, the Lamassu’s legacy endured. The Achaemenid Empire of Persia (550–330 BCE) embraced the figure, incorporating it into their own architectural and spiritual traditions. The Lamassu’s symbolic fusion of strength, freedom, and wisdom continued to resonate across cultures and centuries.

In Akkadian belief, the human-bull hybrid was associated with Papsukkal, the gatekeeper of the gods and attendant to Anu, the sky deity. Though the Lamassu wore the horned tiara of divinity, it was not worshipped as a god. Instead, it served as a bridge between the mortal and the divine—a sentinel at the threshold of sacred space.

Standing before the Lamassu in the Iraq Museum, I felt a profound connection to the ancient world. This wasn’t just a sculpture—it was a living testament to human imagination, craftsmanship, and spiritual yearning. Its silent gaze seemed to pierce through time, reminding me of the enduring power of myth and memory.

My visit left me with a deep appreciation for the richness of Mesopotamian civilisation and the artistry that continues to inspire awe. In the presence of the Lamassu, I was humbled by the magnitude of human ingenuity and moved by the timeless beauty that still speaks to us today.

Amazing artifacts! I hope they last the test of time. Thanks for sharing!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Riley.

LikeLike

You’re welcome!

LikeLiked by 2 people

I have seen these figures in the encyclopedia and also when I read about this region. So, this was much before Islam swept across the region? It looks like in many ways this civilization was much more advanced and evolved than the current religion which is quite rudimentary

LikeLiked by 1 person

That was the time when all great civilisations like, Roman, Greek, Egyptian, Mesopotamian, Persian and Indian, reached their heights, but the mankind couldn’t maintain the development. You can note the details in the reliefs, which show their skills and cultural diffusion. We are still wondering how the people at that time would have constructed the majestic ziggurats, pyramids. How the astronomers studied and marked the movement of celestial bodies with such precision without any telescope, etc.

LikeLike

Indrajit, I have all reasons to believe that all these civilizations were highly developed and had attained some sort of sophistication Which is completely missing in the current times…. In the entire middle East. To me it looks like the current civilization is without any sophistication.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree with you, Arvind. History has shown that it’s a cyclical process and let’s hope that the humanity will reach its zenith again.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I hope so. It’s actually strange to know that people don’t even talk about Mesopotamia and Persia, Which was once a great civilization. Egypt is the only country which has been able to encash some bits along with Greece and Italy. Religion and politics seems to be the culprit in this scheme.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes Arvind, I agree with you.

LikeLiked by 2 people

🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

It is great to see that these artifacts were safe from the barbarian invaders in the middle ages and are intact as opposed to the ones that we see in India, vandalized by the invaders.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Aro, the situation is rather very bad in Iraq, unfortunately. Many of the thousands of years-old artefacts and remnants of ancient civilisations have been vandalised by invaders, looted by greedy people, lost due to ignorance or apathy and these happened till recently. After the US invasion in 2003, even the museums were looted and artefacts were sold and smuggled out. The last blow came from ISIS when they devastated and demolished the artefacts, remains of the buildings etc and we all watched those videos helplessly. Lamassu, of course, is impossible to loot because of its size and weight. Many artefacts are now safe in museums in the US, London, Paris and Baghdad. Read my next post on the National Museum of Iraq.

LikeLike

Thanks for this informative post and an engaging conversation! Loved it. 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, Balroop.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: The Iraq Museum: Refuge for relics of the past – Indrosphere

Thank you, sir, for sharing this interesting post on Lamassu, the sacred guardian figures of the city and throne in ancient Mesopotamia. There was a pair of these figures in the British Museum.These half-bull half-human figures are very noticeable. I think there is a pair somewhere in Mumbai too.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, Somali. You can see Lamassu in the Fire temple of Parsis in Fort, Mumbai.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes, I must have passed by a number of times but I think Non-Parsis are not allowed inside the Fire temple.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I also don’t think they allow non-Parsis to enter inside the Fire temple, but you can see the temple from outside with Lamassu standing there to welcome you. 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

Pingback: Winged Genie of Assyria – Indrosphere

beautiful

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, sir.

LikeLike

Pingback: Unearthing Enchanted Guardians: The Living Lamassus - Nishi Chandermun